Sofonisba's Chess Game - Sofonisba’s Style (2/9)

Not so easy to assess

When you think of the artists you admire, chances are that the first things that springs to mind are the unique aspects of their style: the way they create their figures, or their use of light or colour, or their innovative choice of background landscapes, or something else entirely. From Michelangelo’s powerful, twisting characters to Giacommetti’s famously wiry sculptures, an artist’s uniquely captivating style invariably plays a principal role in capturing our attention and turning us into ardent fans.

And while a signature trait of successful artists is their restless dynamism that manifests itself as an ongoing stylistic evolution, such a progression nevertheless almost always occurs within a consistently coherent overall context, leading the informed viewer to make increasingly confident assessments of whether any given work belonged to an “early” or “late” period of artistic development.

With Sofonisba Anguissola, however, the story is much more complicated, for a number of different reasons.

Bursting onto the mid-16th century Northern Italian scene as a dazzlingly precocious female talent, the young Sofonisba created an impressive array of high-quality portraits, many of which her ambitious father sent as gifts to the great and the good in order to establish her artistic reputation.

It was a strategy that bore considerable fruit, judging both by contemporary literary references that glowingly refer to her remarkable artistic prowess, and even more significantly, the fact that she was selected by the powerful Habsburg king Philip II to become a painting instructor, and lady-in-waiting, to his new wife Elizabeth of Valois – an offer she took up in 1559, when she moved from Cremona to the Spanish court.

All very impressive. But what about her style?

Well, here’s where it gets very interesting.

Sofonisba established herself as a particularly sensitive and captivating portraitist, repeatedly demonstrating a technical and psychological understanding well beyond her years.

And while several of her subjects were local luminaries or those from further afield who briefly passed through her Cremona home, the majority of her surviving early works were either self-portraits or portraits of other family members (such as The Chess Game).

So on the one hand you might well say that Sofonisba’s style is linked to her preternatural ability to construct particularly revealing personal studies that somehow manage to convey fundamental personality traits of the sitter; and that she had an evident fondness for self-portraiture.

Which certainly wouldn’t be wrong.

On the other hand, it’s awfully tempting to think that the reason why Sofonisba made so many self-portraits in the first place (along with repeated portrayals of her many sisters) was simply because that was the only way she could appropriately develop her artistic skills, particularly at the beginning of her artistic career, before she became sufficiently famous to attract a diversity of different sitters.

In fact, one could go even further and speculate that the principal driving factor behind why she specialized in portrait painting in the first place (which was, according to the sentiment of the day, hardly at the top of the artistic hierarchy – a position occupied by grand historical narratives and large-scale religious and mythological scenes) was because, as someone in the exceptionally unique position of being a young female painter of a noble background, portraiture was the only significative artistic option open to her.

Now of course that hardly means that she disliked doing it; and judging by her unparalleled skill in that domain, and several of her surviving remarks – such as what van Dyck later passed on from his meeting with her – that clearly wasn’t the case. But, used as we are to the modern-day notion that artists are completely unfettered in their choice of subject matter, it’s definitely worth bearing in mind that 16th-century artists – and particularly female artists – were a good deal more constrained than we might naively assume.

Artistic style, in other words, is hardly independent of personal and historical context – a point that Sofonisba goes on to demonstrate even more vividly once she arrives at the Spanish royal court a few years later.

Because while we have a few examples of paintings that seem very much like natural extensions of her pre-Spanish period – such as this lovely self-portrait (or so I like to think),

the vast majority of works attributed to her from her years in Spain are effectively indistinguishable from the more formal, impersonal style of Alonso Sánchez Coello, Philip II’s official Court Painter.

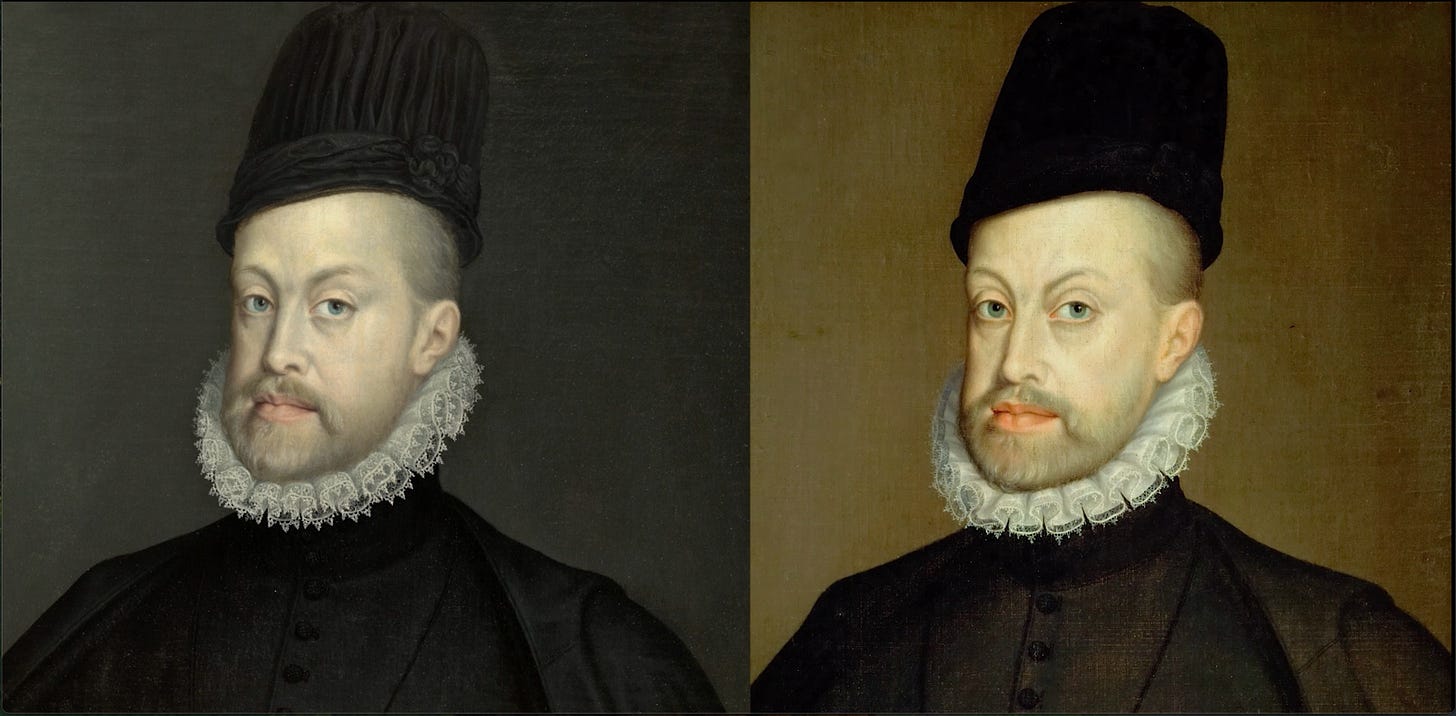

A particularly vivid demonstration of this fact can be seen from examining the following two portraits of Philip II,

with the one on the left, in the Prado, currently attributed to Sofonisba, while the one on the right, from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, believed to be by Coello. Presumably one was made as a copy of the other. But how can we be certain which one came first? And perhaps more to the point: does it really matter?

Given such overwhelming pictorial evidence, it’s hard not to conclude that, upon coming to Spain, Sofonisba deliberately decided to adapt (“strongly tempered” might be a more apt phrase) her style so as to be completely in sync with the prevailing artistic traditions of contemporary Spanish court culture. Which also goes some distance towards explaining why, in striking contrast to her earlier work in Cremona, none of the surviving paintings from her Spanish period were signed.

That’s not to say, of course, that Sofonisba’s unique interpretive skills were completely submerged during her Spanish period. Here, for example, is her compelling portrait of Elisabeth of Valois,

generally regarded as having been created years later after an initial sketch she made during her time in Spain. For me, at least, it vividly exemplifies Sofonisba’s trademark ability to capture the unique character of the sitter, with its penetrating simultaneous depiction of both confidence and vulnerability.

But unfortunately we can’t be 100% certain that she actually painted it.

Howard Burton

Below is the trailer of our new film Sofonisba’s Chess Game.

Exclusive offer: Paid subscribers will be able to watch this film ahead of its official release later this month. If you have not subscribed yet (free or paid), make sure to subscribe now to quality for a free pass - at the end of September we’ll select 15 subscribers.

Fascinating deep dive into an artist's story. About the fact that women were relegated to a lesser rank in the hierarchy of painting, I made a similar point with Elizabeth Vigée Lebrun.