Angelic Insights

The joy of halos

My first serious exposure to art came in my mid-twenties when I was in London for a physics program at Imperial College, and in my usual unfocused fashion wound up spending far more time in the National Gallery than I did attending my courses.

Perhaps the most wonderful thing about living in a place where you have free access to world-class art every day is that you can take your time. After a few months of intense wanderings throughout the Gallery’s masterpiece-laden corridors, I fell into the habit of dropping by for just an hour or so – sometimes even less – devoting all of my time and attention to just one or two works.

But my new-found enthusiasm only went so far. Whenever I’d encounter an early devotional work, I’d quickly hurry past, regularly shaking my head in wonder at how such “primitive displays of artistic ineptitude” could have so abruptly given way a mere few centuries later to the explosion of creative genius lining the walls a few rooms away.

With the opening of the Sainsbury Wing devoted to late medieval and early Renaissance art, my policy of wholesale avoidance of signature altarpieces became easier still: for decades I only went “over there” to visit the café, lecture theatre or gift shop.

These days, ironically enough, I spend almost all of my time poring over images of works created before 1400 – some of which, unsurprisingly, are to be found in that very same Sainsbury Wing.

Why the sudden switch? Well, it began as a sort of professional obligation: I’ve recently decided to make a series of films about in situ Italian art; and for me, at least, the most reasonable way to proceed with such a project is chronologically. So I rolled up my sleeves and tried hard to understand why so many art historians kept going on so rhapsodically about artists like Cimabue and Duccio and Giotto, none of whom had ever personally moved me in the slightest.

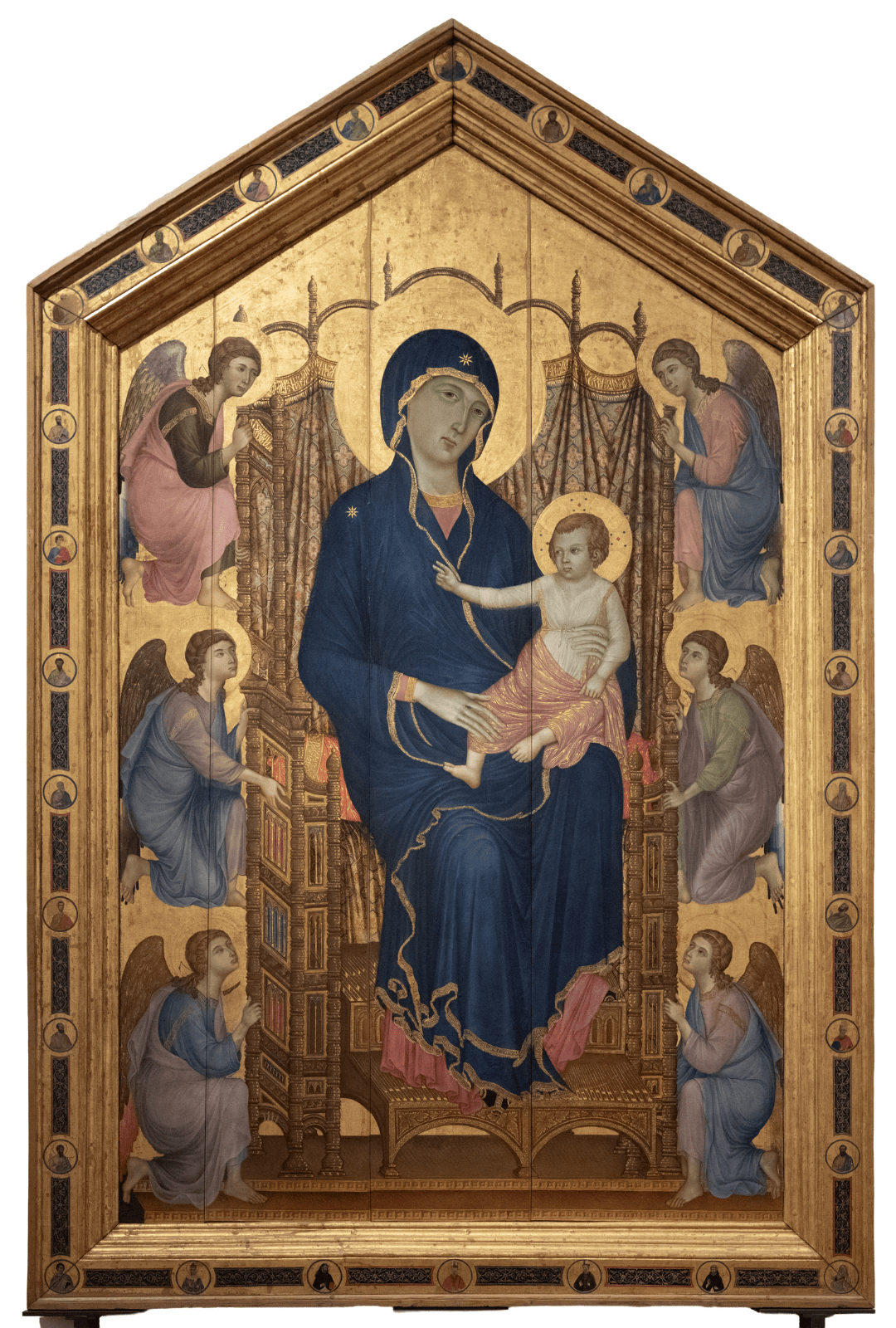

When I started these investigations several months ago, my understanding was very dry and theoretical. Duccio’s celebrated Rucellai Madonna (1285), I learned, was the product of Byzantine and French Gothic traditions, fully in keeping with his other famous late 13th-early 14th century Italian contemporaries. But on a personal level the painting itself, with its stiff, formal poses and clunky large halos, did nothing for me.

And then I took a closer look.

It started, in fact, with those halos. Why was it, I wondered, that those belonging to the top four angels were in front of the Virgin’s throne and thus appeared to “cut into” it, as opposed to those of the lower two that were so clearly behind it? A few moments later I noticed that it’s actually rather more complicated than that: the top two angels have both their head and protruding foot in front of the throne, the middle angels have their head in front and their lead foot behind, and the lower angels have their head behind and lead foot in front – a most intriguing set of symmetrical positioning.

From there I turned to their dainty, well-positioned hands grasping the sides of the Virgin’s throne; then the remarkably intricate folded cloth background of the upper level of the throne itself, and then the captivatingly cascading golden hem of the Virgin’s mantle that culminated in a spectacularly convoluted array, complete with her subtly protruding foot – a feature, I would later learn, replete with a world of fascinating connotations in its own right, as the noted art historian Joanna Cannon has so eloquently revealed.1

Was it mere coincidence that the lower part of the Virgin’s throne contained precisely the sort of “arched geminated windows” so often seen throughout Duccio’s home town of Siena that so forthrightly regarded itself as the “city of the Virgin”? Likely not. Details, glorious details, everywhere.

Meanwhile, the longer I gazed at the face of the Rucellai Madonna, the more I began to appreciate that she was quite exceptionally beautiful. That her long sculpted nose and almond-shaped tapered eyes derived from the well-recognized Byzantine iconic tradition was both indisputable and somehow irrelevant: her mournful, knowing look was clearly all her own, and profoundly distinct from the faces of the surrounding angels – themselves reflective, beautiful and dreamily compelling. Stiff formal poses? I couldn’t have been more wrong.

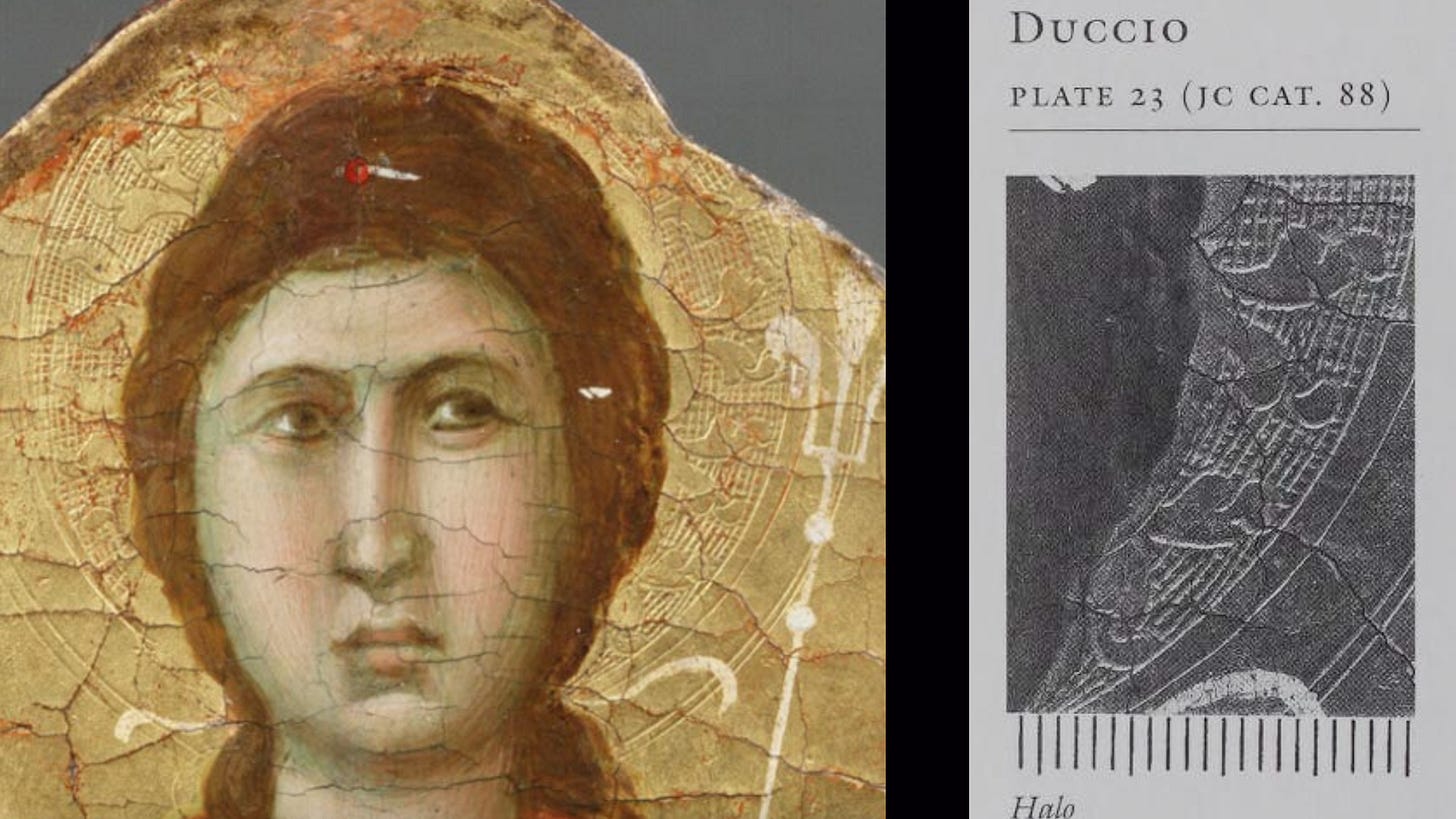

And then – once again – I returned to those halos. They’re not, as it turns out, simply solid globes as I had once thought, but instead inlaid with mesmerizingly intricate patterns that had been carefully, rigorously, inserted into the surrounding gold ground. This is hard to discern in a standard lower-resolution image of the enormous Rucellai Madonna – but trust me, they’re there.

One of the most accomplished creators of such intricate decorations was Duccio’s student Simone Martini, as can be seen from these magnificent patterns in the halos of Gabriel and the Virgin in the famous Annunciation he made with Lippo Memmi.

Art historians, resourceful people that they are, have looked very carefully at the so-called “punch marks” in these halos for decades.

From the founding work of Mojmir Frinta and Erling Skaug2 to modern classification efforts using deep neural networks3 , punch mark analysis has long been a thriving aspect of scholarly research that is actively used to shed valuable light on key issues of attribution, workshop techniques, contemporary influences and much more.

In short, these “clunky, large halos”, as I once thought of them, turn out to be remarkably useful. But much more than that: they are, first and foremost, spectacularly beautiful.

I know that now. But only because I took the time to look.

Howard Burton

🎬 We’re currently in pre-production research of an extensive range of art films that will be filmed on location in Italy. All films are based on meticulous research and a strong narrative in combination with a wealth of beautiful images and filmed materials to provide viewers – from the armchair traveller to visitors to Italy to students and scholars – with a highly-informative and fully accessible exploration of Italian Renaissance art.

🎙️ 🎥 Make sure to subscribe for further updates about new films and also about our brand-new art history video podcast!

Absolutely brilliant piece on rediscovering what we've dismissed. That detail about punch mark patterns being used for attribution studdies is fascinating because it reveals how "decorative" choices held real functional purpose for workshops. I had a similar moment with illuminated manuscripts thinking the gold leaf was showing off until I realzied it manipulated light in dim churches. Sometimes slow looking changes everything.