Gothic Gobbledygook

When words get in the way

One of the most challenging aspects of plunging into a new field is being forced to navigate your way through the complexities of an entirely new vocabulary.

Most of the time this is eminently reasonable, as such words and expression invoke fundamental conceptual issues upon which our contemporary understanding depends: if you don’t know what apoptosis or gauge invariance mean, you won’t just be unable to sound like a biologist or physicist, you won’t have the slightest hope of comprehending what any modern cancer researcher or cosmologist is actually doing. It’s as simple as that.

In art history, on the other hand, many of the words and labels customarily thrown around often seem like something quite different: an unhelpful jargon whose fundamental utility seems dubious at best and downright obfuscatory at worst, going a considerable distance to needlessly bamboozle the curious neophyte.

One of my favourite examples of this sort of thing is the notion of “Gothic”, a term that surely everyone who has taken the slightest interest in European art or architecture has frequently encountered. But what the hell does it actually mean?

Well, it’s very far from clear.

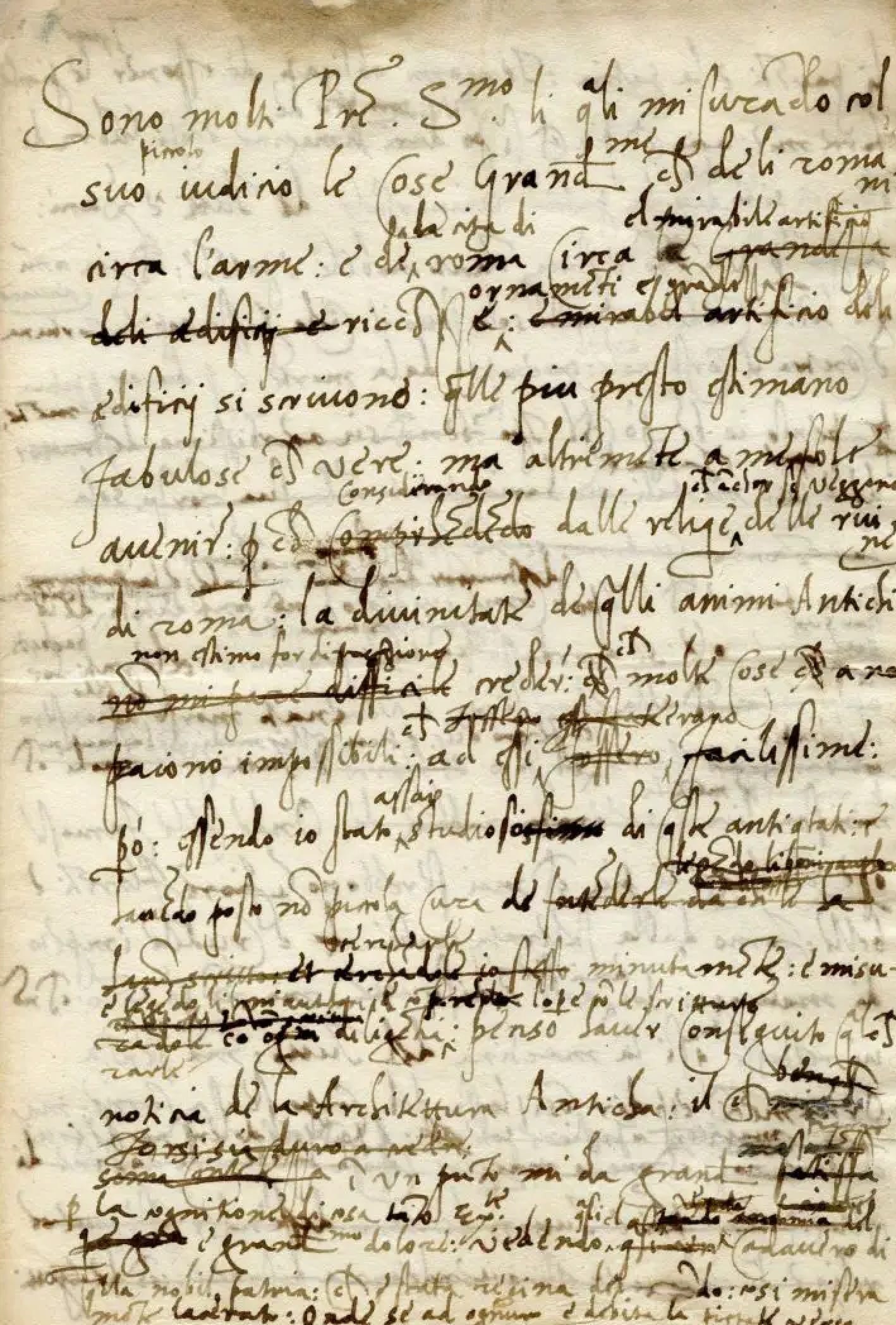

Right off the bat, to the uninitiated it certainly sounds like something negative – unrefined, uncouth and uncivilized. And, indeed, that was precisely the meaning it had when it first made its appearance on the artistic scene over 500 years ago, in Raphael and Baldassare Castiglione’s famous Letter to Leo X, where they urged the pope to take action to protect the rapidly decaying ancient ruins throughout Rome.

To Raphael and Castiglione, two of the most celebrated representatives of their age – one in the visual arts and the other in the literary – all the architectural efforts from the fourth to fifteenth century (more or less) were eminently forgettable products of a disastrously long period of decline precipitated by those who had wantonly destroyed the glorious achievements of Ancient Rome.

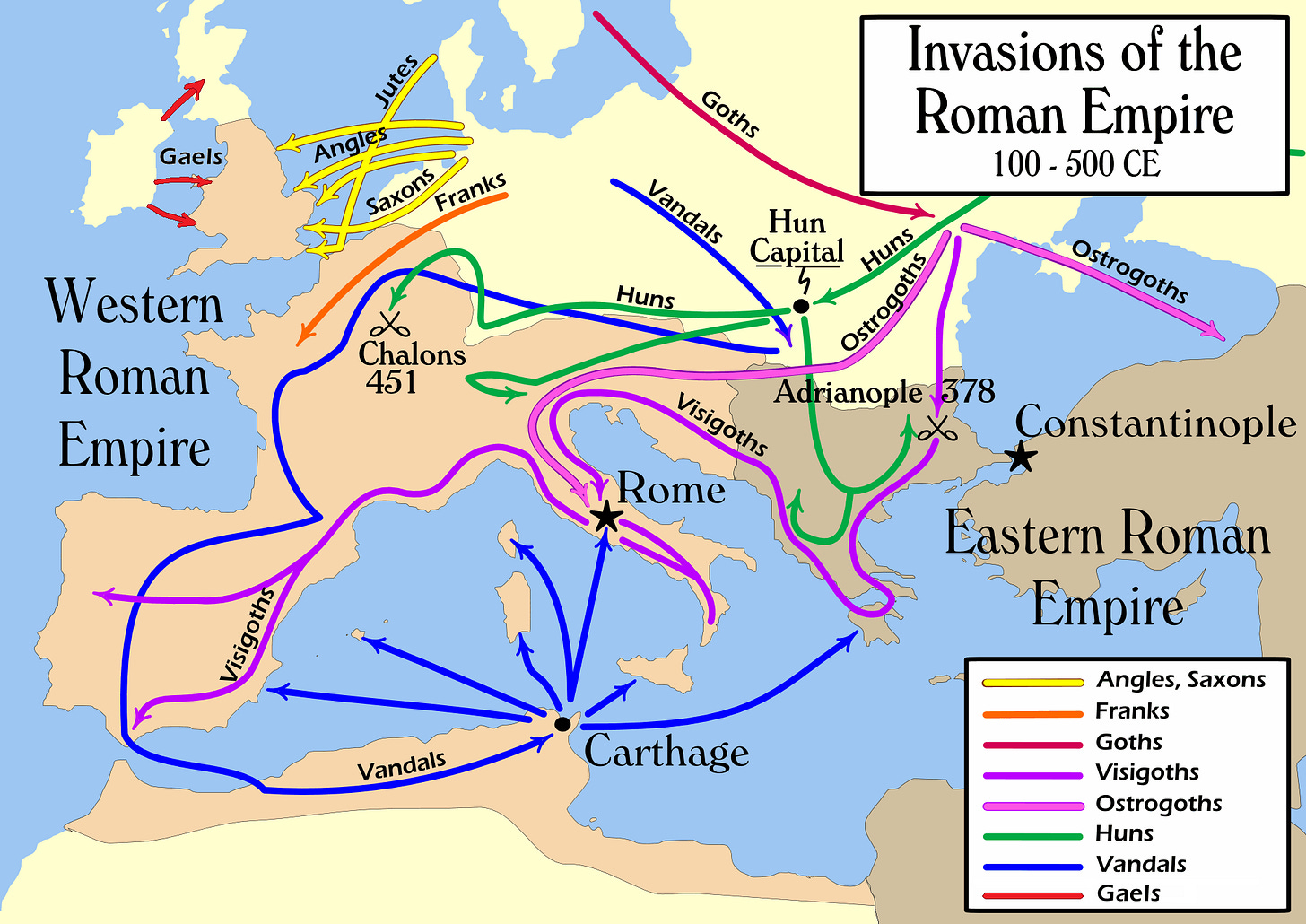

This then, was the legacy of the “Goths” - those rampaging hordes who had shamefully plunged the civilized world into more than a millennium of the most profound cultural darkness ever known, our long night of aesthetic despair that had only been overcome by the glorious spirit of the Renaissance that Raphael and Castiglione were so actively contributing to.

Now, one can certainly take issue with their rather simplistic characterization,1 but at least it bears some basic measure of historical accuracy. After all, the Roman Empire did finally succumb to an insurmountable series of invasions of barbarian tribes from the north and east, most conspicuously the Germanic Goths (further subdivided into Visigoths, Ostrogoths and what have you).

So in the same way that the current English word “vandalize” has its roots in another invading Germanic tribe of the epoch, and the “Goths” at your high school are characterized by their predisposition for consistently donning black apparel and makeup, for most of us there’s a coherent, albeit grossly simplified, historical thread associated with the notion of “the Gothic”.

But not for art historians.

In the first case, there’s a significant difference between the relatively well-defined “Gothic architecture”, the decidedly more vague “Gothic sculpture” and the downright nebulous “Gothic art”.

Let’s begin with architecture – which was, after all, the target of Raphael and Castiglione’s initial use of the term all those years ago.

Gothic Architecture

Any basic textbook will tell you that Gothic architecture is an architectural style that became prevalent throughout much of Europe in the 12th century, characterized by such common characteristics as high, crenellated spires and prominently arched windows

– the sort of features, in other words, that were explicitly revived in the 19th century “neo-Gothic revival” that rapidly sprawled out in many different directions,

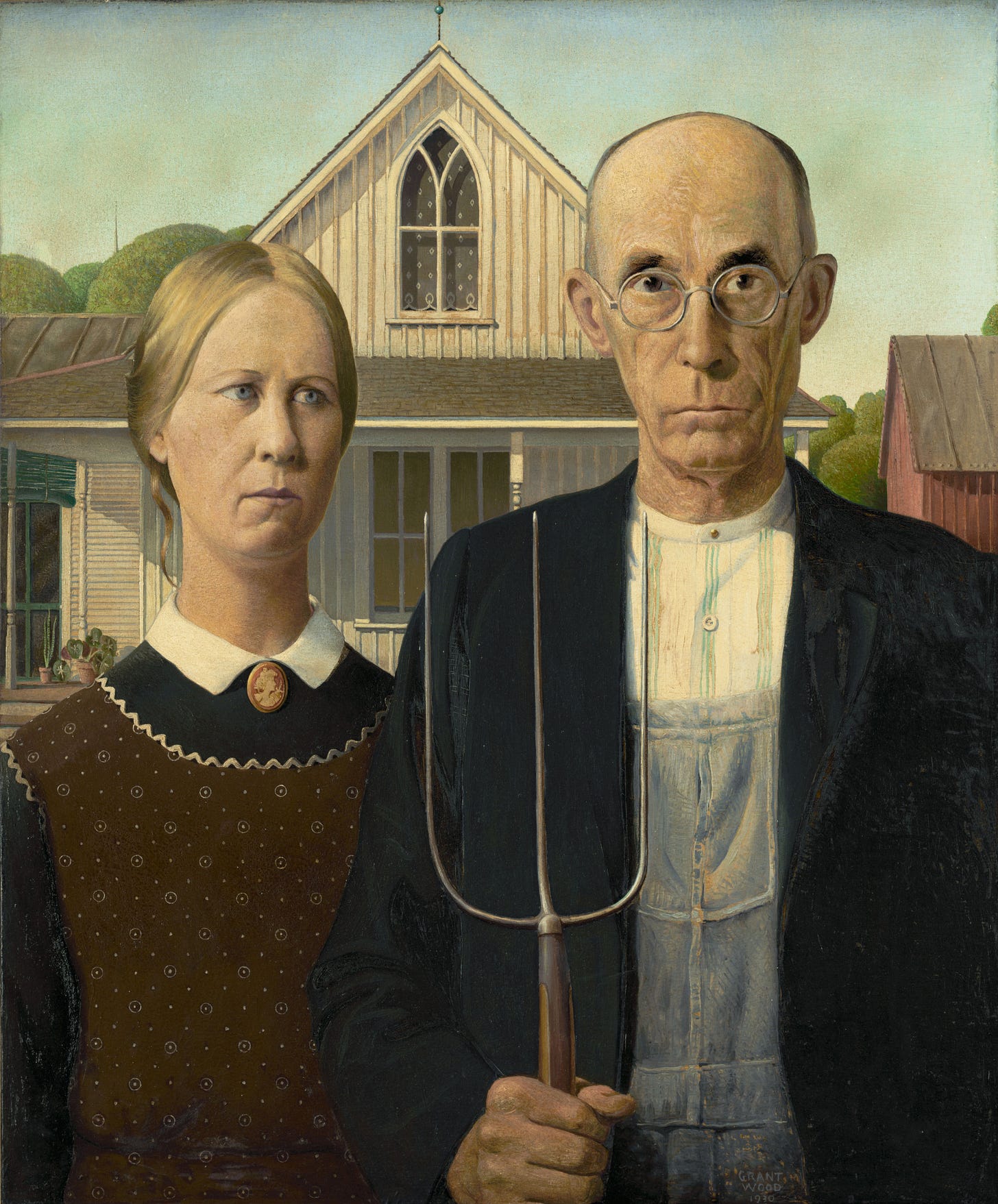

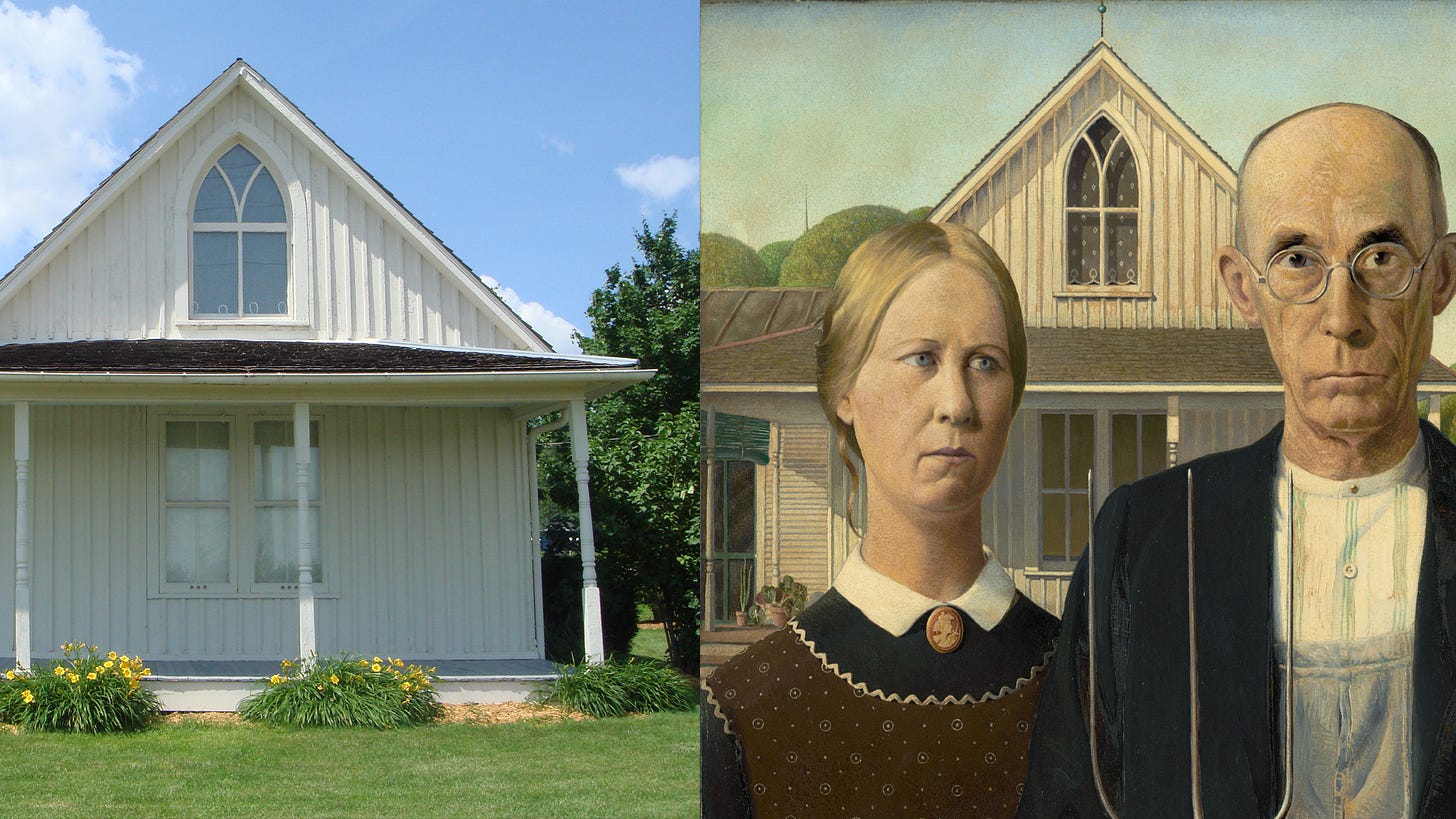

eventually leading Grant Wood to create his iconic painting, American Gothic.

Wood was struck by the pretentiousness of an explicitly ogive Gothic window on the upper level of a modest Iowan farmhouse he encountered, known as The Dibble House (apparently the style is known as “Carpenter Gothic”). As a consequence, he deliberately painted the window as narrower than it really was, while the faces of the two figures and the pitchfork the man is holding (reflected on his overalls) explicitly emphasize the vertically-oriented, famously pointed characteristics of the “Gothic style”.

Well, cataloging all those common architectural features is certainly helpful – something, clearly, is stylistically going on here – but it’s nonetheless all pretty misleading. Because to really understand what Gothic architecture represents, it’s vital to compare it to its immediate predecessor, which is commonly called Romanesque. At some point builders recognized that they could construct stable structures using only a fraction of the necessary supporting material that they once thought was required, thanks to their innovative “rib vaults” (and, later, the so-called “flying buttresses”), leaving substantial new scope for much higher structures replete with large, beautiful windows, that offered a much brighter and more overwhelming spiritual experience than had ever occurred before.

In other words, the fundamental distinguishing aspect of Gothic architecture – its principal experiential feature that anyone who has ever walked into a Gothic building is immediately aware of – is the brightness and airiness of its interior (as well as its sheer imposing size).

If it strikes you as ironic and not a little confusing for a 12th-century architectural movement single-mindedly driven by a desire for light and space to be named after a 3rd-4th-century Germanic tribe consistently associated with darkness, you’re not alone.

But then it gets even more muddled.

Gothic Sculpture

At least the term “Gothic sculpture” has some sort of relative coherence associated with it, if one simply regards it – as is often the case – as a way of collectively describing stylistic aspects of the statues found on the exterior of the great Gothic cathedrals. But the problem, of course, is that such sculptural styles changed considerably during such a long time period. Those on the Chartres Cathedral created in the mid-12th century, for example, are naturally quite stylistically different from the ones placed on Siena’s Cathedral a century and a half later.

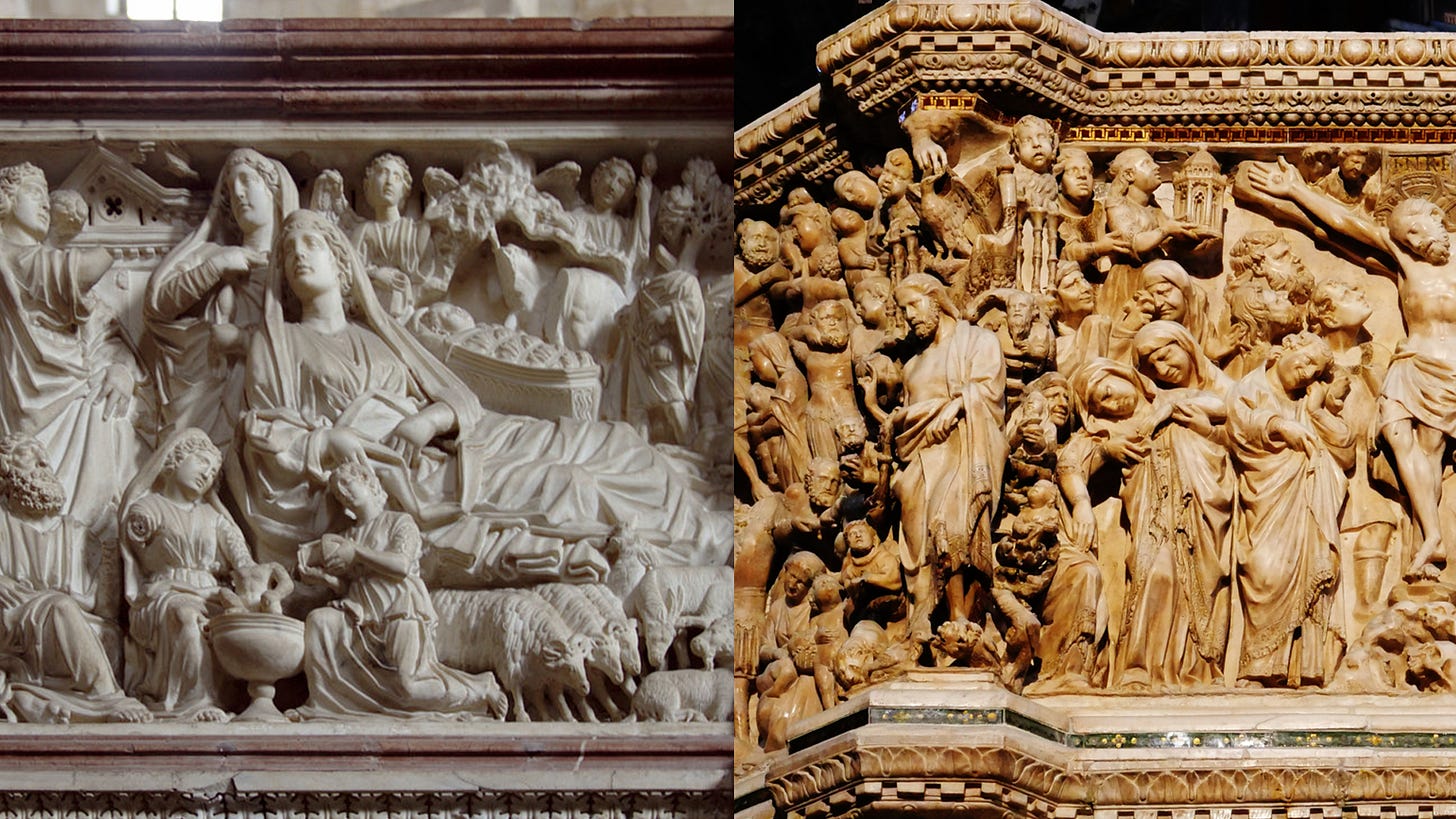

Moreover, if all I mean by “Gothic sculpture” is “sculptures found on Gothic cathedrals”, it’s not clear what, precisely, I’m gaining by invoking the term in the first place. Take Nicola Pisano’s famously innovative pulpits in both Pisa’s Baptistery and Siena’s Cathedral. Sure, we can tautologically call them “Gothic” because they were made in the 1260s, but that doesn’t actually do anything to help us understand their uniqueness. What makes them special, why so many people justifiably regard them as a fundamental turning point in the history of art (and what so obviously distinguishes them from most other sculptures that were made at precisely the same time), is the way that they so beautifully and movingly combine ancient Roman sculptural traditions with modern Christian iconography.

Gothic Art

But if the notion of “Gothic sculpture” is unhelpful, the broader category of “Gothic art” (painting, stained glass, frescoes, illuminated manuscripts) is little less than a miasma of incoherence, containing, as it does, oblique references to so many different artistic aspects – Byzantine traditions (or lack thereof), linear perspective (or lack thereof), narrative inclinations (or lack thereof), crowded pictorial planes (or lack thereof), and thousands more – that is wholly bereft of any explanatory utility whatsoever.

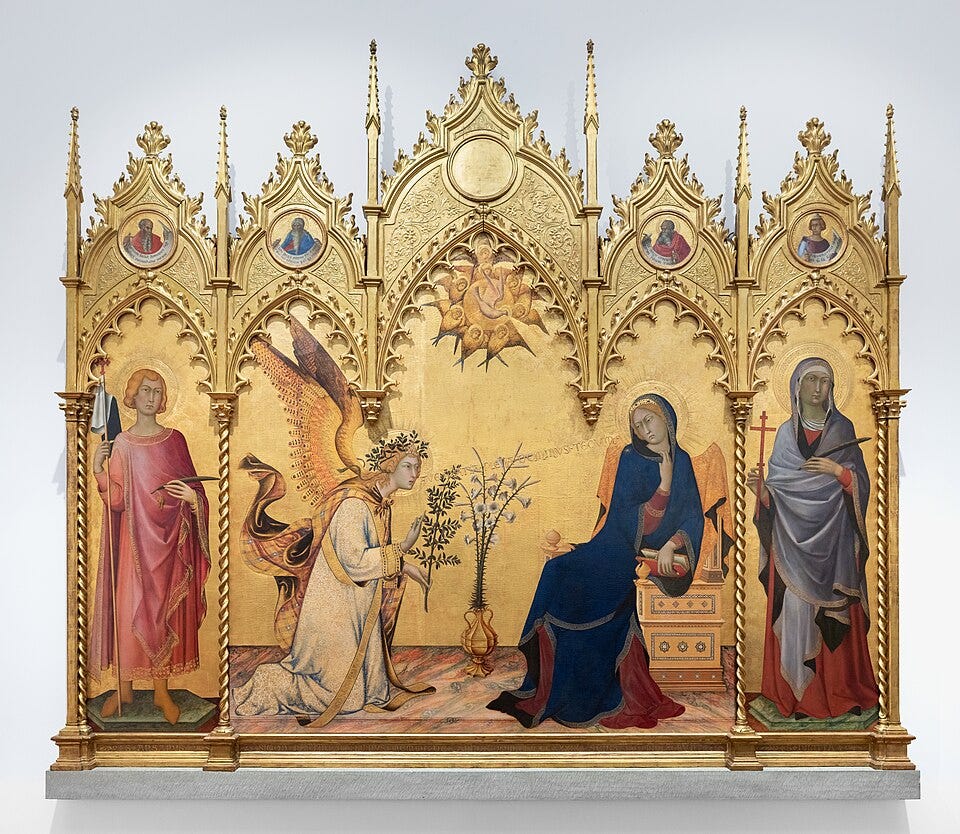

Simone Martini, we’re blithely informed, was a Gothic painter.

What does this mean? Was he more or less “Gothic” than the Lorenzetti brothers, his great Sienese competitors, or his older famous contemporaries Duccio, Giotto and Pietro Cavallini? And if so, how exactly? Positively unclear. All we’re told is that Martini’s move to Avignon in the last decade of his life was a major contributing factor to initiating the “International Gothic” movement that supposedly “spread Gothic artistic ideals north of the alps”.

To any earnest soul out there still diligently trying to make sense of all this categorical nonsense who might be thinking, Hang on a minute, wasn’t the “Gothic art movement” actually supposed to have started “north of the alps”, in France, in the first place? I’ve got some advice for you.

Do yourself a favour: drop the word “Gothic” from your artistic vocabulary and just look closely at what’s in front of you.

Howard Burton

🎨 We’re currently in pre-production research of an extensive range of art films that will be filmed on location in Italy, starting with Florence, Siena, Pisa, Padua and more.

🎬 All films are based on meticulous research and a strong narrative in combination with a wealth of beautiful images and filmed materials to provide viewers – from the armchair traveller to visitors to Italy to students and scholars – with a highly-informative and fully accessible exploration of Italian Renaissance art.

I've often wondered if this deliberately unnuanced castigation of "barbarian Germanic forces" in the 1519 letter to Pope Leo X was also a thinly-veiled allusion to Martin Luther's rebellious rumblings that were beginning to generate significant public momentum by that point – but I've never seen any scholar mention anything about that whatsoever, so I'm likely entirely off base there.

I love "Drop the word Gothic and just look at what's in front of you", it applies to so much jargon. Sometimes categories obscure rather than clarify. Thanks for this!

Absolutely, I have been saying similar things for a long time, and recently in my Sainte Chapelle story.

Labels like 'Gothic' are like gluing Post-it notes on buildings, statues, and paintings.

The silliness, as you rightly mention, goes on with "International Gothic", Rayonnant Gothic, Flamboyant Gothic, and so on, all of it the fresh stuff coming out of cows.

These labels do not help the art lover understand why a particular statue, painting, or building is special.