Sofonisba's Chess Game - Searching for Clarity (6/9)

Sisterly confusions and attributional fluctuations

We’ve seen in my previous essay, Passing It On, how the importance of teaching others was a core value of the Anguissola household, one that eventually resulted in most, if not all, of Sofonisba’s five sisters becoming highly accomplished artists in their own rights.

This is, to put it very mildly, deeply impressive.

But it also considerably clouds our detailed understanding of both Sofonisba’s paintings and their precise historical context, not least of which because the Anguissola sisters strongly resembled one another.

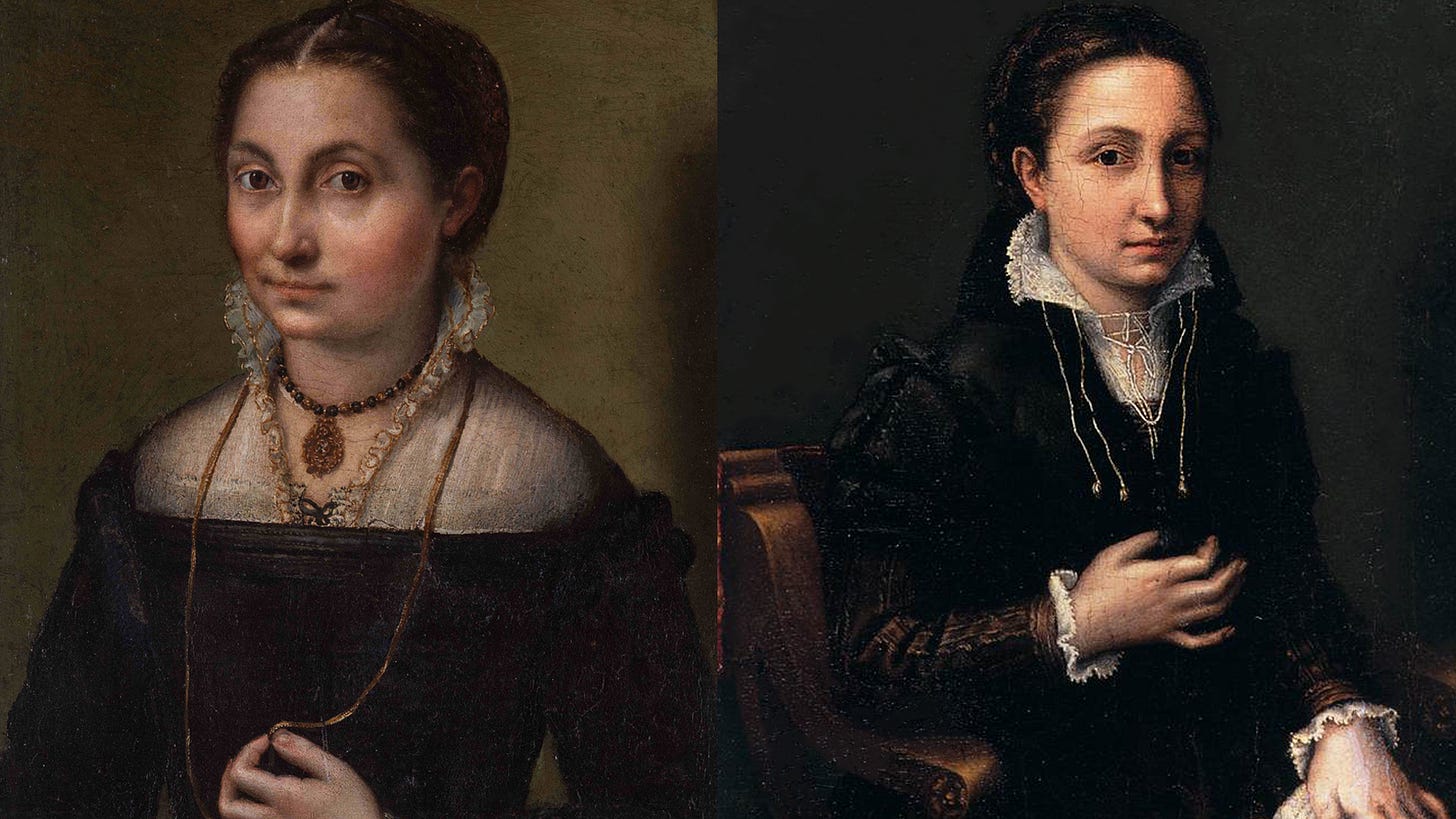

Below, on the left, for instance, is a portrait that experts have universally identified as one by Sofonisba, but the sitter has long been a matter of doubt, with some maintaining that it’s a self-portrait and others believing it to be a depiction of her sister Minerva.

Personally, I’m convinced that it’s meant to depict Minerva, given its strong resemblance to another of Sofonisba’s portraits in Milwaukee widely believed to represent her (centre), with both figures striking me as a straightforwardly older version of the younger Minerva presented to us in The Chess Game, on the right.

Then there are two works presently in the Uffizi: a miniature oil tondo and a chalk drawing, with beliefs on the identity of the sitters typically fluctuating between Sofonisba herself and her sister Lucia (although there are also those who maintain that the miniature is a portrayal of someone outside the Anguissola family entirely).

In particular, those who argue that the drawing represents Lucia will frequently justify their belief by the dreamy, faraway look in the figure’s eyes that seems to be similarly invoked in the portrayal of Lucia in The Chess Game and in her Woman at the Keyboard (where the maid in The Chess Game once more makes an appearance, this time in the left background).

So far we’ve been dealing with paintings that the vast majority of specialists agree were indeed created by Sofonisba. But there are also many cases where attribution has shifted over time from Sofonisba to one of her sisters.

The Portrait of a Woman below on the left, for example, in Rome’s Galleria Borghese, was long attributed to Sofonisba, but is now generally believed to be by Lucia Anguissola, largely due to stylistic and contextual similarities with Lucia’s well-documented self-portrait.

And then there’s this painting,

which for years was straightforwardly attributed to Sofonisba, with the added conviction that the figures represented are (from left to right) the three youngest Anguissola siblings: Europa, Asdrubale and Anna Maria.

But for my money, it doesn’t really look much like a Sofonisba; and in any event if the children represented here really are Europa, Asdrubale and Anna Maria Anguissola, they would have all been much younger than the ages shown here when she left for Spain in 1559. And it doesn’t look to me much like something by Lucia either. So maybe…Minerva?

Meanwhile, this small work below on the left, also in Rome’s Galleria Borghese, was also long attributed to Sofonisba given the sitter’s obvious similarity to Sofonisba’s portrait of a nun on the right, currently in Southampton’s City Art Gallery.

Personally, it seems pretty unquestionable that the sitter is the same, but equally clear that the work on the left is by someone else, as it doesn’t strike me as having nearly the quality of the Southampton portrait – an opinion that also seems to resonate with the powers that be at the Galleria Borghese, as they’ve recently reattributed to Elena Anguissola as a self-portrait, the only extant work I know of that’s currently believed to be by her hand.

But perhaps the most intriguing “wandering sisterly attribution” story of all involves this painting of an elderly woman in Copenhagen’s Nivaagaards Malerisamling Museum.1

For centuries considered Sofonisba’s “last self-portrait”, now, thanks to rigorous detective-work by the indefatigable Michael Cole (see here), it has recently been convincingly re-attributed to Europa Anguissola.2

Of course, given Sofonisba’s longstanding status as a 16th-century artistic phenomenon who often didn’t sign her work (particularly once she left for Spain), there are also many vigorous debates about her potential involvement in works that don’t involve any of her sisters .

This self-portrait, for example,

currently at the Uffizi Gallery, has long been viewed by many as suspect, due to the simple fact that, quite frankly, it simply doesn’t look like it’s up to Sofonisba’s high artistic standard (it has an inscription, as you can plainly see; but inscriptions can obviously be faked).

Meanwhile, a little over twenty years or so ago, this 16th-century altarpiece,

was declared with much fanfare to be a lost work of Sofonisba from the five years she spent in Paternò, Sicily. The Ala Ponzone Museum in Cremona devoted an entire 2022 exhibit to it, and Finestre sull’Arte breathlessly announced: “Our Lady of Itria, the only certain Sicilian Work by Sofonisba Anguissola.”3

Well, it turns out that it it’s not so certain, after all, as there are many good reasons to suspect4 that Sofonisba didn’t paint any of it, not least of which because it is – how should I say it? – not really all that impressive.

Lady In a Fur Wrap, on the other hand, in Glasgow’s Pollok House, is an unquestionably striking painting.

It, too, was sometimes attributed to Sofonisba, and even more often believed to be by El Greco. But in 2019 researchers concluded that it was the work of Alonso Sánchez Coello, the official court painter to Philip II, at least partially due to its obvious similarity to another painting attributed to him at the Prado, Portrait of an Unknown Young Woman – also, not coincidentally, once believed by many to be by Sofonisba.

Lastly, there is the story of this magnificent painting of Alessandro Farnese.

Purchased by Dublin’s National Gallery of Art as a work by Alonso Sánchez Coello, it has now been re-attributed to Sofonisba as the first work by a female artist acquired by the Gallery, albeit inadvertently.

All of which, I’m convinced, serves to highlight a vital point. As fascinating as it is to immerse oneself in the detailed detective work of trying to track down who, exactly, painted what about whom, we should never lose sight of the fact that an artistic work should always stand on its own, independent of the authority of its alleged creator.

Paintings like the Portrait of Alessandro Farnese or Lady in a Fur Wrap or Portrait of the Artist’s Mother in Law are very much worth looking at, not because we are reasonably certain at this moment that they are by Sofonisba or Coello or Europa, but because they are so intrinsically captivating.

Which is really the whole point, no?

Howard Burton

Below is the trailer of our new film Sofonisba’s Chess Game.

Exclusive offer: Paid subscribers will be able to watch this film ahead of its official release later this month. If you have not subscribed yet (free or paid), make sure to subscribe now to quality for a free pass - at the end of September we’ll select 15 subscribers.

Which also contains a famous bonafide Sofonisba, as it happens, the Portrait Group with the Artist’s Father Amilcare Anguissola and her siblings Minerva and Astrubale – which, along with The Chess Game, Vasari famously saw, and commented most favourably upon, during his visit to the Anguissola household in the mid-1560s after Sofonisba had moved to Spain and Lucia had died.

The curious reader is once again directed to this 2023 talk at Washington’s National Gallery of Art for more details.

Captivating indeed. I need to see the portrait 'Lady in a Fur Wrap' in real life one day, it looks terrific.

About the difficulty of identifying portraits, particularly when there are five sisters, I was putting the finishing touches to my next article, about Susanna Fourment, sister of Helena Fourment, Rubens' second wife... It will be published on Monday.