Sofonisba's Chess Game - Why Chess? (4/9)

An illustration of values

In my initial post in this Sofonisba series, Choosing Sofonisba, I mentioned that Sofonisba’s Chess Game was strikingly different from virtually all other paintings in the “chess art” genre, given that none of the characters (other than the maid on the far right) were actually looking at the board, leading us to naturally conclude that the work was about much more than chess itself.

And there are other aspects of this painting that go a considerable distance towards supporting this hypothesis as well.

Consider the clothes that Sofonisba’s three sisters (Lucia, Europa and Minerva from left to right) are wearing, along with their magnificently detailed jewelry – hardly the sort of apparel that one might casually throw on to play a chess game in the back yard.

It seems pretty clear that, rather than presenting a game in progress to represent the intellectual inclinations of the protagonists or the absorptive power of chess itself, Sofonisba is instead determined to offer us a carefully constructed portrait of three of the Anguissola daughters, appropriately decked out in their best sartorial finery.

And not just individually. Because one of the most compelling aspects of Sofonisba’s Chess Game is how they interact as a group, with the youngest, Europa, clearly relishing the sudden discomfort of Minerva, who’s just realized that she’s committed a potentially catastrophic blunder on the board and vainly appeals for mercy from her eminently self-controlled senior sibling, Lucia.

This painting, in other words, doesn’t just represent a temporal snapshot of three daughters of different ages, but the overarching family values of the entire Anguissola household, with its emphasis on the painstaking acquisition of serene self-mastery.

We know that their father Amilcare, proud of his noble heritage yet constantly suffering from considerable financial pressures, nonetheless went to great lengths to ensure that his 7 children – six daughters and one son – received the best possible education.

In his 1609 biography of Sofonisba, the Valencian writer Pedro Pablo de Ribera writes:

“As Amilcare was a lover of knowledge and virtue, he wished for his daughters to occupy themselves in such things as well, and Sofonisba thus pursued various things, especially music, letters, and above all painting”

A claim that is clearly reinforced by a spectrum of self-portraits of Sofonisba vigorously representing each of these activities.

So where, exactly, does chess fit into all of this?

Well, we know that in the mid-16th century, chess was in the midst of one of the many popularity booms that it has undergone over the ages,1 this time sparked by the sweeping changes to the motion of the queen and bishop that had occurred some 75 years earlier.

These modifications abruptly transformed what had long been a slow, stately game to a swashbuckling affair of rapid attacks and complex strategies, where untrained players could swiftly find themselves on the receiving end of a devastating attack – exactly like what seems to have happened to the young Minerva, who raises her hand at evident dismay of suddenly finding herself in a hopeless position.

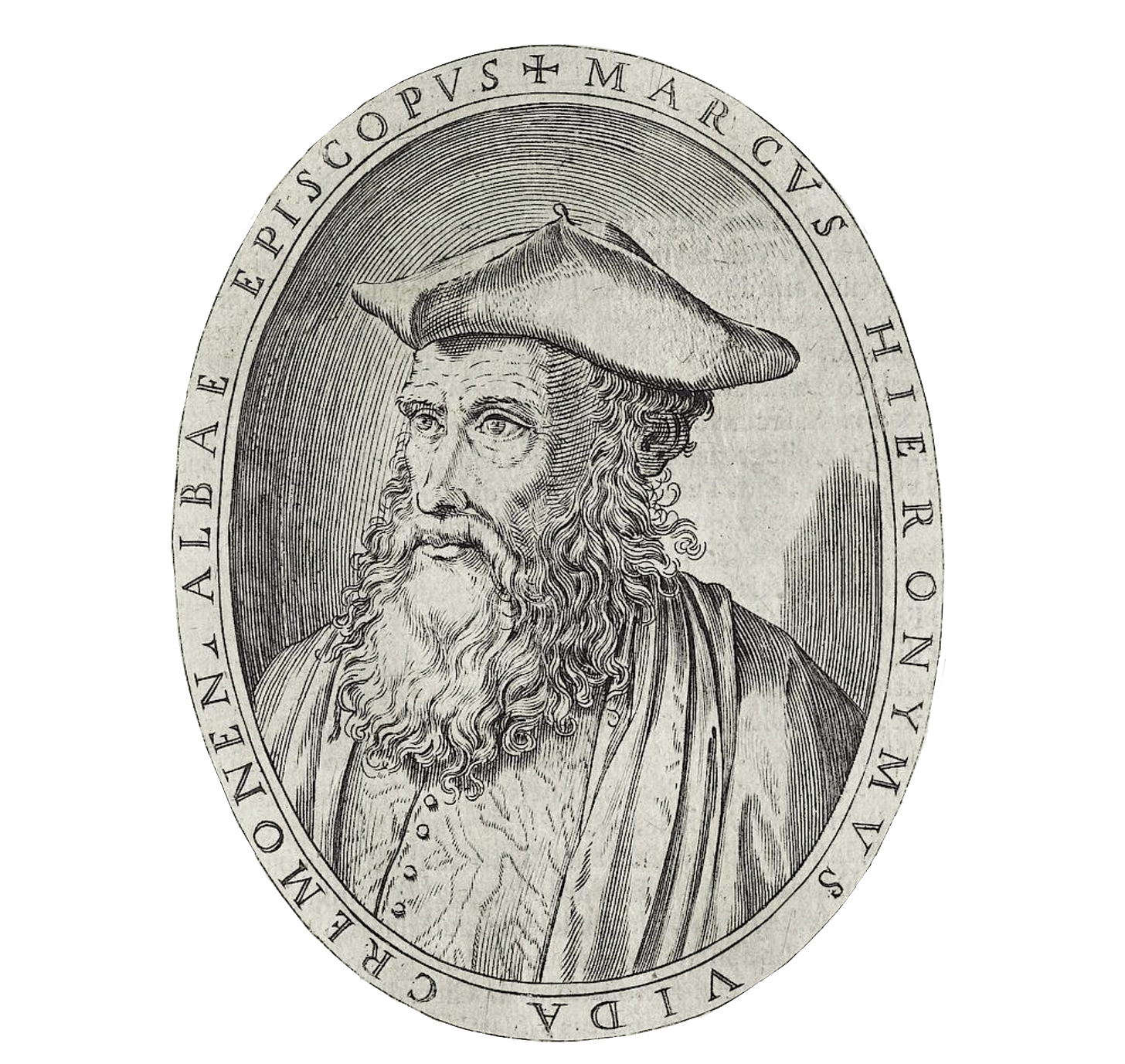

This new version of chess (sometimes called “queen’s chess” or even “mad queen chess”) was rapidly adopted by the upper classes as a sophisticated pastime fully resonant with their prevailing humanist values, as witnessed by the popularity of the 1525 Latin poem Scacchia Ludus, where chess is given a classical origin myth featuring a game between Apollo and Mercury on Mount Olympus.

Scacchia Ludus, intriguingly, was written by the celebrated humanist and Bishop of Alba, the Cremona-born Marco Girolama Vida, who happened to have been an acknowledged friend of Amilcare Anguissola, and who famously trumpeted Sofonisba’s universally-recognized artistic reputation in his 1550 treatise, Against the Pavians.2

Given all of that, it’s easy to see how chess would have been a warmly endorsed activity in the Anguissola household, and one deemed fully appropriate for Sofonisba to represent in a family portrait.

But there’s something else too.

Because as anyone who’s ever played the game knows all too well, playing chess can be a painful experience. You think you’re doing fine, and then suddenly, seemingly out of the blue, your more experienced opponent swoops in and rapidly decimates your position.

And from an educational perspective, the key question is: How are you going to react to all of that?

Are you going to angrily storm out of the room, the mocking laughter of your younger sister Europa ringing in your embarrassed ears? Or are you going to swallow your pride and dispassionately analyze the situation so as to be able to better defend yourself from such eventualities in the future – adopting, in other words, the vastly more productive, composed attitude of your elder, calmly unrelenting, sister Lucia?

Because in marked contrast to the modern stereotype so enthusiastically promulgated by Hollywood, success at chess is not a sign of innate intelligence, but rather demonstrates an ability to carefully learn from your past mistakes: a skill which is by no means limited to playing one particular board game, and is essential to mastering any discipline worthy of your time and attention.

That’s why, as I wrote earlier, I’m convinced that Sofonisba’s Chess Game, isn’t actually about chess itself. Instead it uses chess as an ideal tool to vividly represent her family’s overarching educational philosophy of a dedicated striving for objective excellence, a philosophy which enabled her to become one of the greatest portraitists of her age.

All of that in one painting. And some very nice chiaroscuro too.

Howard Burton

Below is the trailer of our new film Sofonisba’s Chess Game.

Exclusive offer: Paid subscribers will be able to watch this film ahead of its official release later this month. If you have not subscribed yet (free or paid), make sure to subscribe now to quality for a free pass - at the end of September we’ll select 15 subscribers.

We seem to be in another one right now, as it happens, with online chess sites such as chess.com and lichess.org being some of the most enthusiastically visited recreational “gaming” sites on the planet.

Along with that of a young female Latin poet, Partenia Gallerati, whom Vita seemed to have actively mentored.