Subjective Expertise

The importance of coming to your own conclusions

One of my favourite aspects of art history is that the more time you give to any given piece of art, the more personally compelling it can become.

The first encounter with any monumental artwork is typically overwhelming in a cool, detached sort of way, but it is only when we force ourselves to linger on its details that we begin to establish our own connection to it.

This is the principal reason, I think, why many of us find standard art tours so disappointing. We trudge through museums and galleries listening to some expert or audioguide tell us stories about what’s in front of us, but we rarely take the time to quietly absorb the impact of the work for ourselves. And at the end of the day what we remember from the experience – if anything – is simply what we’ve heard, not what we actually saw or felt.

I’m not, of course, opposed to the stories. As long as they’re presented as our current level of scholarly understanding rather than the God-given Truth, they offer us a vital historical context of both the art and artist that can dramatically increase our awareness of why and how things were done the way they were.

But those stories should never be a substitute for personal convictions based on our own careful examination – an activity that most of us rarely get around to sufficiently intensely engaging in as we madly scramble to tick off the requisite boxes of our action-packed tourist agenda.

Of course, this is much easier said than done. In addition to the obvious time pressures at play, it takes a certain degree of self-confidence – indeed almost defiance – to force oneself to linger over an artwork that we’re confidently assured is “minor” (if not outright “second-rate”), particularly in an environment bursting with universally-declared masterpieces that we only have a few days (or perhaps hours) to visit.

Which brings me, once again, to Siena’s magnificent cathedral.1 In the fourth chapel up from the entrance on the left-hand side stands the hugely imposing Piccolomini Altar, a multi-tiered marble edifice crafted by Andrea Bregno in the 1480s, complete with its own, separately carved, otherwise daunting but now significantly dwarfed, marble altarpiece in its central niche.2

Six marble statues are displayed throughout. In the top central niche we have a Madonna and Child that is widely, if not universally, attributed to the Sienese sculptor Jacopo della Quercia (1374–1438), believed to have been moved there centuries later from another location in the cathedral. The Saint Francis in the upper left niche was started by Pietro Torrigiani, the artist who’s now most famous for having broken the young Michelangelo’s nose during a scuffle in Florence’s famed Brancacci Chapel, while the other four on the two lower levels – Saints Peter and Paul on the lower left and right respectively, topped by Pius I and Gregory the Great on the upper left and right – are by Michelangelo himself.

Or so we have very good reason to believe.

But for well over two hundred years, various artistic authorities have contested Michelangelo’s authorship of some, if not all, of these statues, while several guidebooks confidently assure visitors that only the Saint Paul on the lower right is really a Michelangelo, leading many artistically-focused tourists to give this spectacular structure only the most cursory of glances as they quickly make their way towards the other unequivocal A-list masterpieces strewn throughout the duomo.

Why do so many art historians have a problem with these statues? The short answer is that many are convinced that they simply aren’t good enough to be considered part of the Michelangelo oeuvre.

Unfortunately for them, however, there’s not one scintilla of evidence to justify such a claim, and a heck of a lot of documentary support in the other direction.

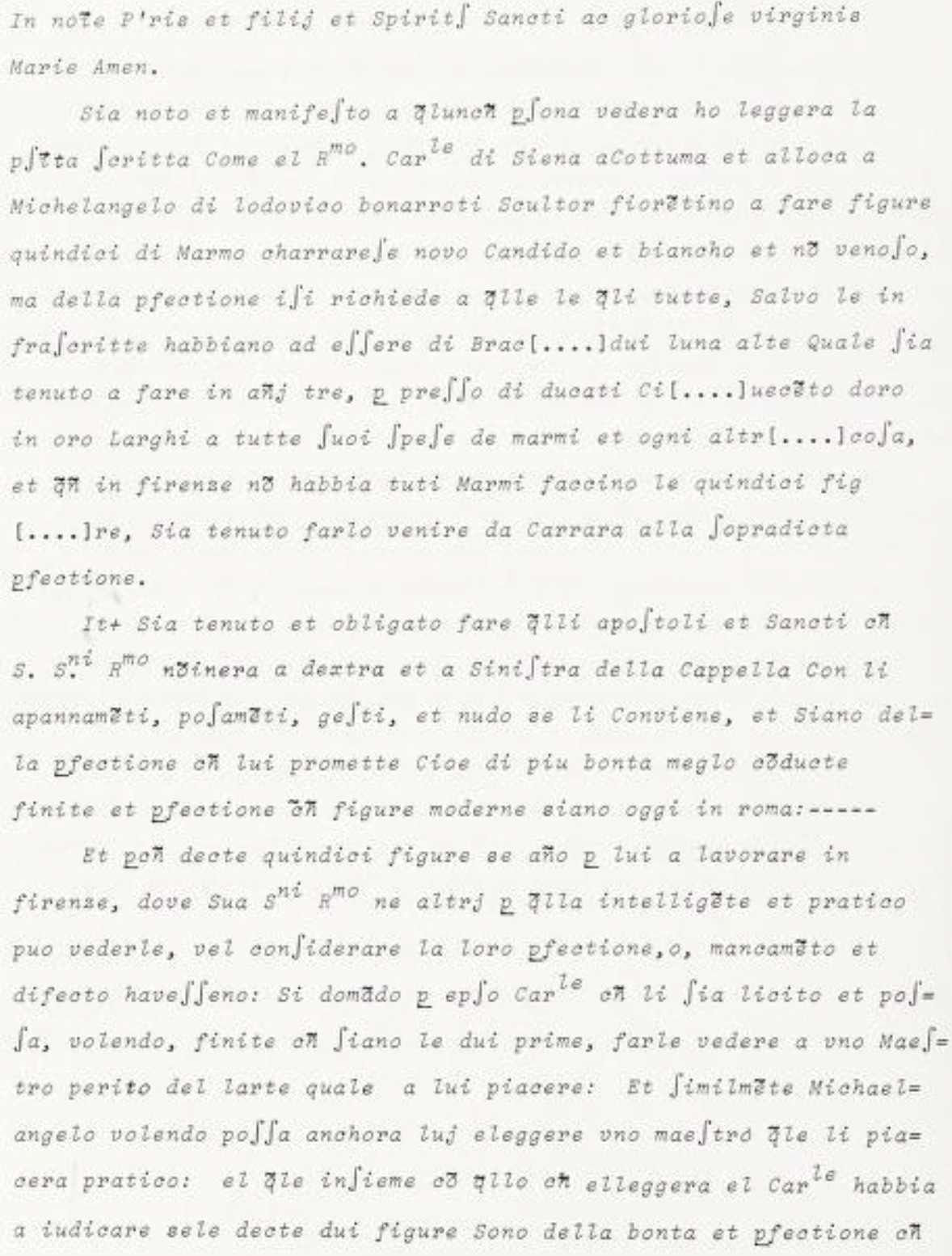

Indeed, Michelangelo’s commission for the Piccolomini altarpiece turns out to be particularly well documented. Not only do we have a copy of the 1501 contract between the famous sculptor and Cardinal Francesco-Todeschini Piccolomini specifying what he was to accomplish – 15 statues of his own and the completion of the St Francis that Pietro Torrigiani began (“since the drapery and head of it are not finished…”) -

we also have a considerable amount of follow-up correspondence over the decades as the commission dragged on. Because, as it happens, Michelangelo only ended up delivering four of the promised 15 statues (along with, it seems, the completion of Torrigiani’s St Francis), all by 1504, never getting around to making any more of the outstanding 11.

Well, he had a good many other things on his plate. Shortly after agreeing to the Piccolomini Altarpiece, the young sculptor who’d been catapulted to artistic celebrity status after having executed his extraordinary Pietà statue a few years earlier, was chosen by Florence’s powerful Arte della Lana guild to resume their long-delayed project of constructing a supersized David for the Florence cathedral (later more prominently installed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria, where a copy of it still stands).

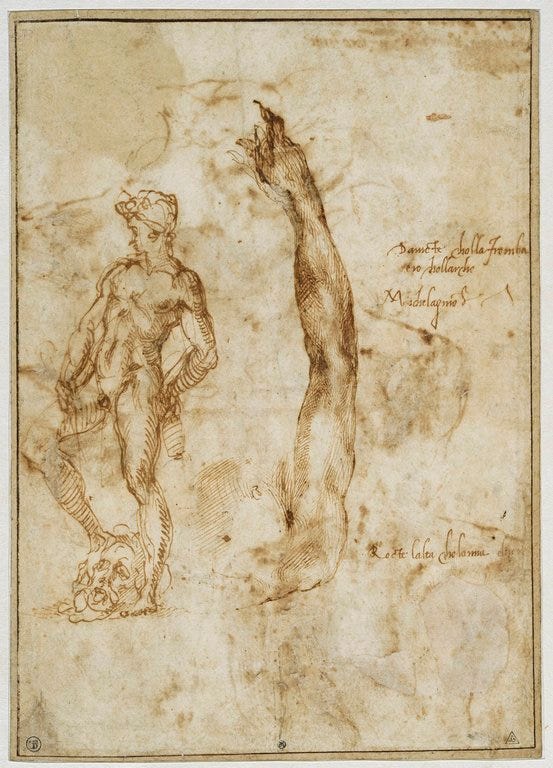

So despite the fact that that 1501 contract he signed with Cardinal Francesco-Todeschini Piccolomini explicitly prohibited him from taking on any other work which might distract him from crafting the Sienese statues, he promptly threw himself whole hog into the more prestigious David commission, together with several others – such as a now-lost bronze David for Pierre de Rohan, for which only a few sketches remain (see below).

Indeed, some speculate that the only reason he ended up turning his attention back to any of the Piccolomini statues at all was because his Sienese patron there was surprisingly elected pope in 1503; and after he died shortly thereafter, Michelangelo quickly sent off four hastily constructed statues to his heirs before turning his attention back to his other, rapidly mounting, commissions.

Well, perhaps.

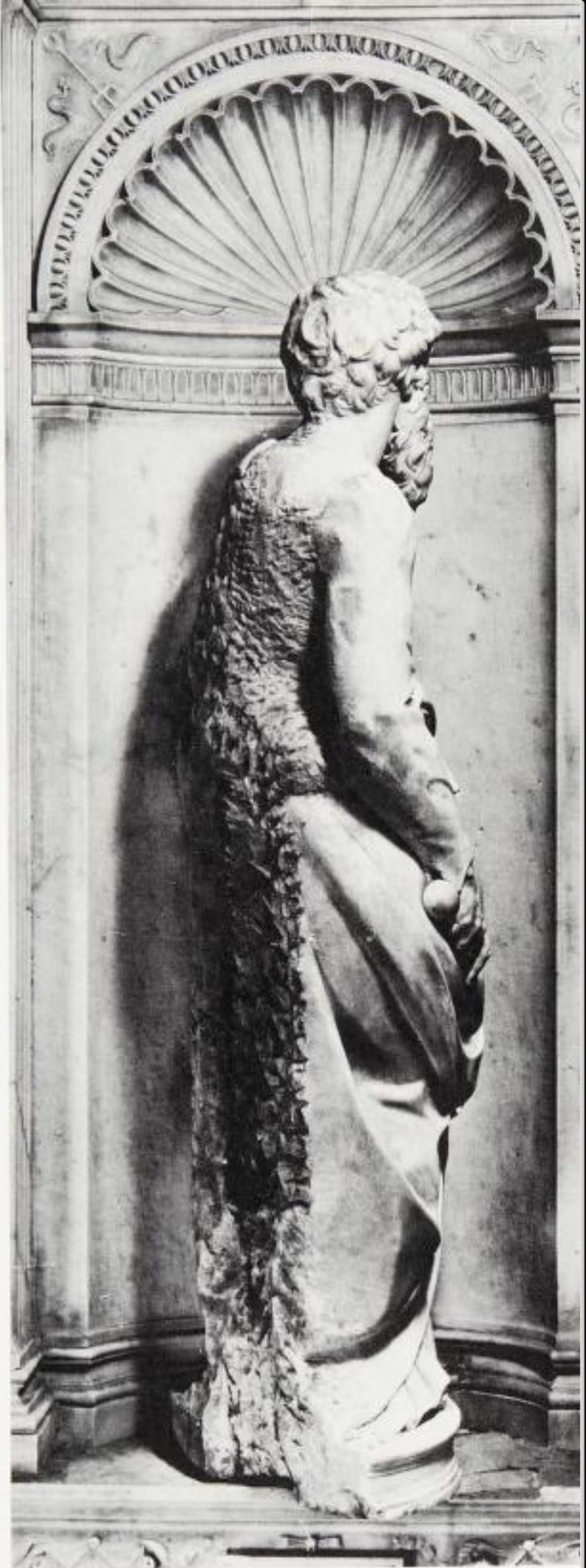

But while there’s certainly an argument to believe that Michelangelo might well have dashed off some aspects of his Piccolomini statues due to the pressure of his other commitments – the backs of all four were unfinished, for example, albeit perhaps not so surprisingly given their niched location – there is still an enormous amount in these works to carefully savour.

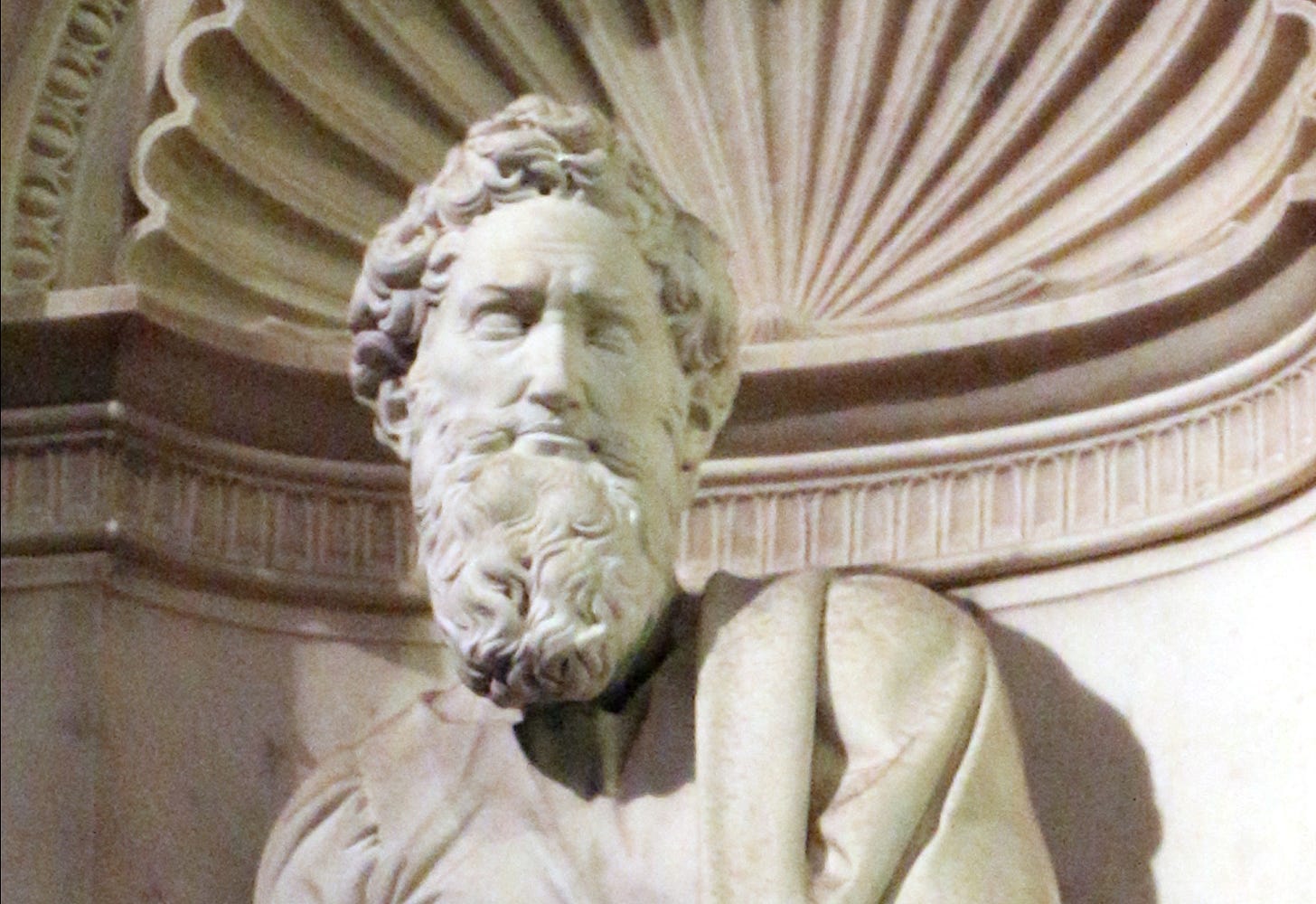

The meticulously crafted drapery of all four figures is little short of outstanding, while the grimly determined face of St Paul has prompted some experts to conclude that it is nothing less than Michelangelo’s first sculpted self-portrait.

Others, meanwhile,3 have pointed out that the nose of the Pius I figure bears an unmistakable similarity to that of the Virgin in the incomplete Pitti tondo, also created by Michelangelo in the early 1500s, but much more commonly embraced by Michelangelo aficionados.

As usual, in other words, expert opinion is divided: while most Michelangelo scholars seem anxious to sweep the whole story of the Piccolomini statues under the art historical rug, several highly-respected researchers adamantly maintain that they’re a key part of Michelangelo’s oeuvre whose merits have been shamefully neglected.

For the rest of us, that’s both expected and largely irrelevant. After all, professional art historians aren’t there to tell us what to think, but to provide us with the most illuminating contextual background possible to sharpen our visual understanding.

But first we have to look very carefully ourselves.

Howard Burton

🎨 We’re currently in pre-production research of an extensive range of art films that will be filmed on location in Italy, starting with Florence, Siena, Pisa, Padua and more.

🎬 All films are based on meticulous research and a strong narrative in combination with a wealth of beautiful images and filmed materials to provide viewers – from the armchair traveller to visitors to Italy to students and scholars – with a highly-informative and fully accessible exploration of Italian Renaissance art.

The attentive reader may recall that I also referred to Siena's spectacular duomo – a masterpiece-satured venue if ever there was one – in last week's piece, Slandered By History. Expect more of the same in the weeks ahead: I'm currently knee-deep in matters Sienese as part of our pre-production research for our new series of art films, and there is no end in sight. Try as I might, I can’t even seem to leave the cathedral and move on to the many other stunning Sienese locales like the Palazzo Pubblico or Santa Maria della Scala. It’s positively unfair how much beauty exists throughout Italy.

Which bears a distinct structural resemblance to Bregno’s Borgia altarpiece in Rome’s Santa Maria del Popolo church created a decade or so earlier.

See, for example, Michael Hirst’s 2000 Burlington Magazine article, “Michelangelo in Florence: ‘David’ in 1503 and ‘Hercules’ in 1506” and Friedrich Kriegbaum’s 1942 paper, “Le Statue di Michelangiolo nell’altare dei Piccolomini a Siena”.