Syncretic Brilliance

The power of continuous coordination

Despite my best efforts, I still find myself, metaphorically if not yet literally, in Siena’s magnificent cathedral. This is hardly a disaster, of course, but it does sometimes make me wonder if I will ever move on. Several months ago I ambitiously resolved to produce a large portfolio of short films showcasing in situ art throughout Italy, focusing on frescoes, sculpture, stucco, mosaics and numerous architectural features.

I excitedly made notes about the wonders of Pisa, Padua, Prato, Pistoia, Piacenza, Pienza, Perugia, Pesaro – not to mention the hundreds of other beautiful art-laden Italian locales that began with letters of the alphabet other than “P”. It was stupendously intimidating, but somehow, I told myself, manageable, as long as I took it slowly and methodically – this is, after all, a multi-year project. Florence, I broke into smaller neighbourhoods; and when even that proved too overwhelming, I switched to individual buildings. Step by step.

And then I hit Siena.

I’m not sure, exactly, what I expected. A long detour, I suppose, but nothing like the inescapable visual black hole that I’m currently experiencing. So far I’ve begun storyboarding no less than 8 separate, half-hour films – 8! – on the Siena Cathedral alone.

From Nicola Pisano to his formidable son Giovanni, from the great Duccio to Simone Martini to both Lorenzetti brothers, from Ghiberti to della Quercia to Donatello to Michelangelo to Vecchietta to Peruzzi to Bernini, from Pinturicchio to Raphael, almost every major Italian artist you can think of has been involved in beautifying the Siena cathedral.1 It’s hard to know precisely how to measure such things, but it’s very tempting to conclude that there’s no other locale on the planet that can boast more legendary creative forces who’ve contributed to shaping its magnificence.

How, on earth, did this happen?

Well, I certainly can’t say for certain, but after careful reflection it seems to me that what separates the remarkable visual coherence of the Sienese duomo from virtually every other storied artistic venue is a steadfast determination to coherently accrete its visual efforts over the centuries, rather than the all-too-often tendency of those in charge to summarily restart their decorative efforts from scratch when they got the chance.

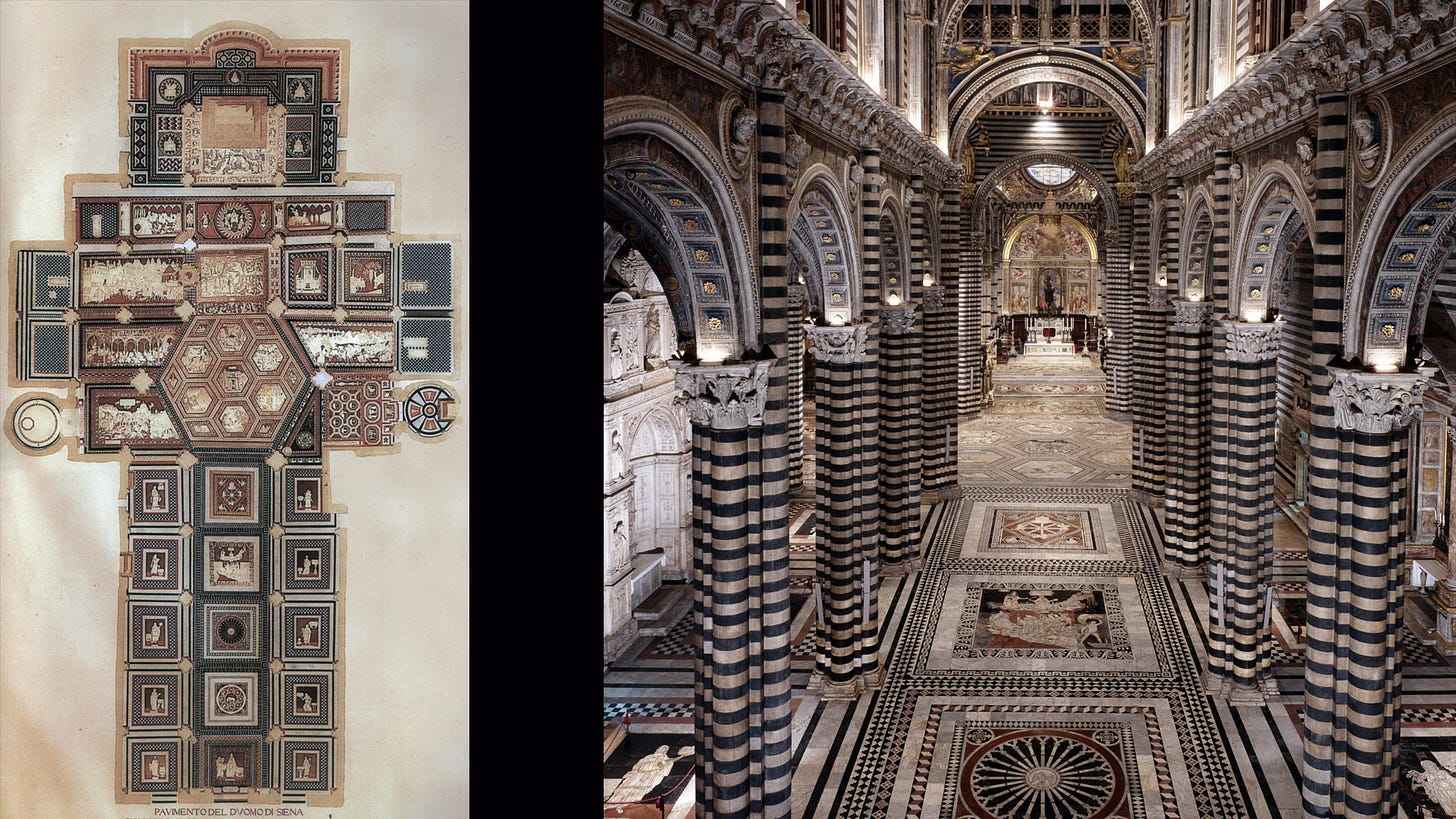

Perhaps the clearest way to see this is through a careful examination of what most believe to be the Siena cathedral’s most stunning visual characteristic of all: its famous pavement mosaics that Giorgio Vasari famously gushed was, “the most beautiful, greatest and most magnificent ever made.”

Many sites and books that concern themselves with this “Wonder of Siena”, as it’s sometimes called, like to muse about who might have first formulated the “artistic program” that gave rise to this beautifully detailed combination of marble intarsia and graffito.2

But the notion that a complex floor pattern that took over 500 years to evolve somehow represents the culmination of some particular “program” not only decidedly strains credulity, it misses a key distinguishing feature – arguably the key distinguishing feature – of the Sienese character that enabled them to construct such monumental works of beauty in the first place.

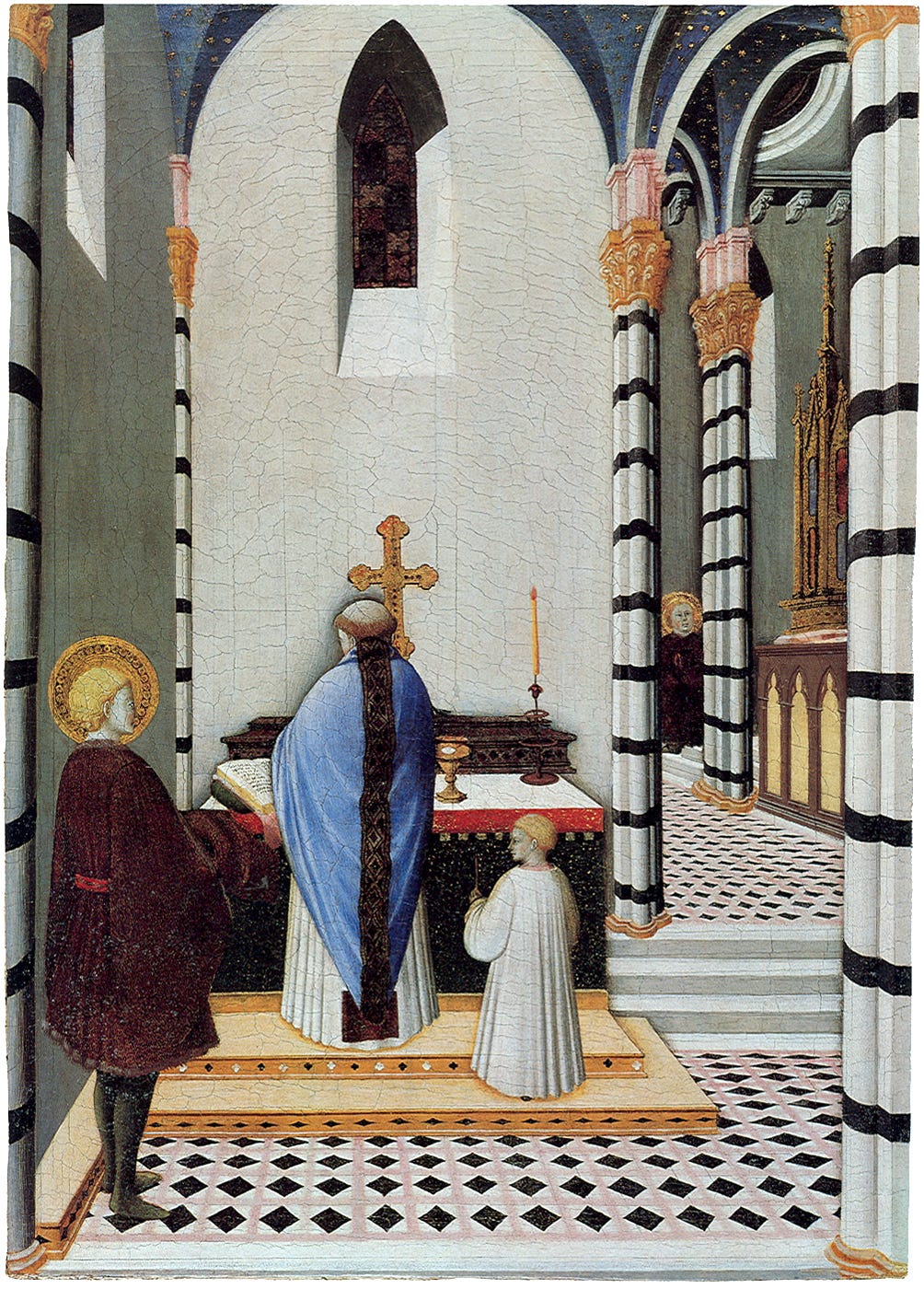

Because there wasn’t, obviously, any one set “program” – a claim that is fully supported, as you might imagine, from the plethora of detailed historical documents.3 So far as we can tell, the story begins in 1310, when the Nine, Siena’s celebrated republic government from 1278 to 1355, released funds for a geometrical mosaic floor patterning of black, white and pink tiles near the cathedral’s high altar, despite considerable expense – which can be clearly recognized from a famous painting of St Anthony Abbott inside the Cathedral by the Master of the Osservanza produced well over one hundred years later.4

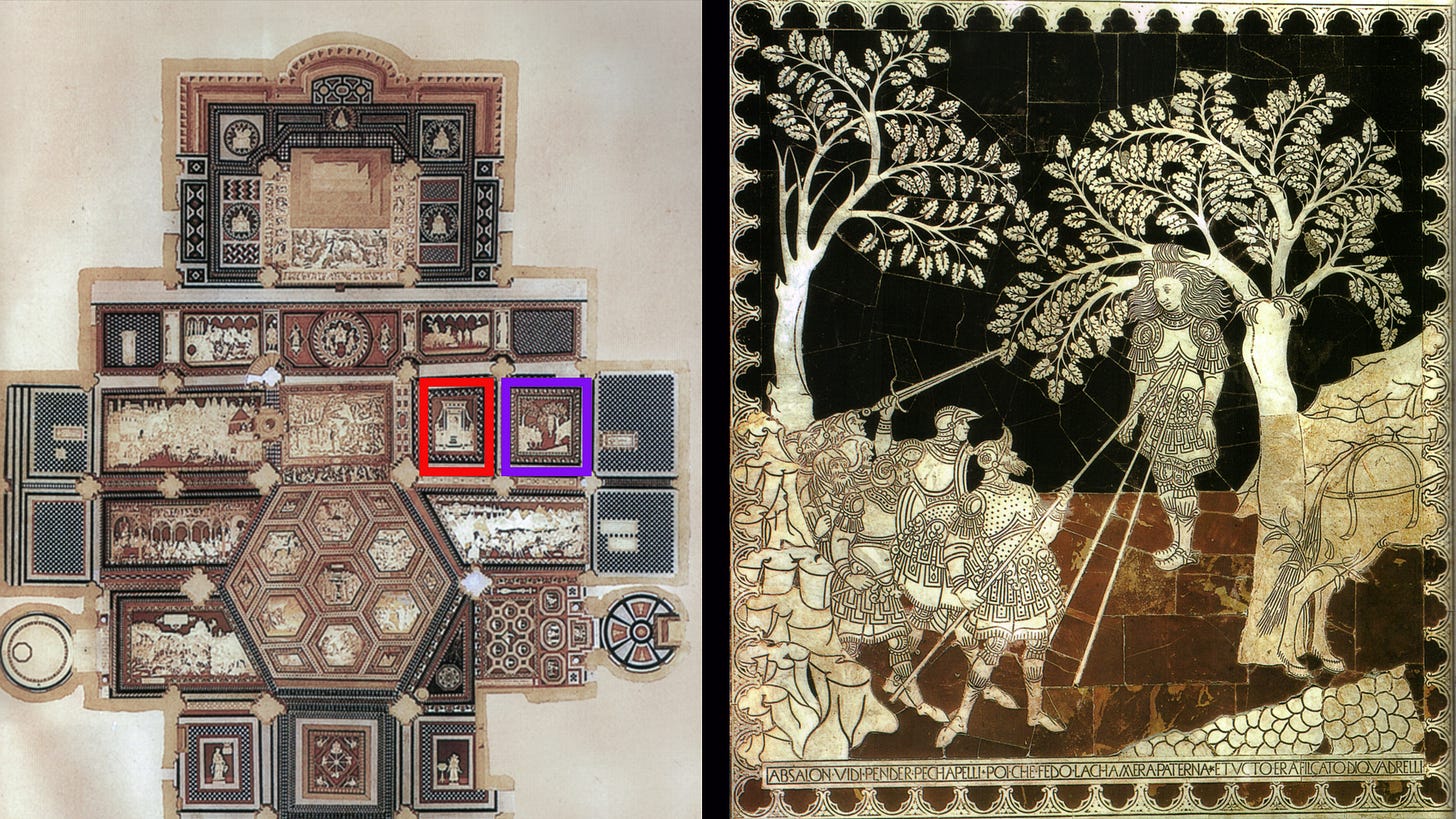

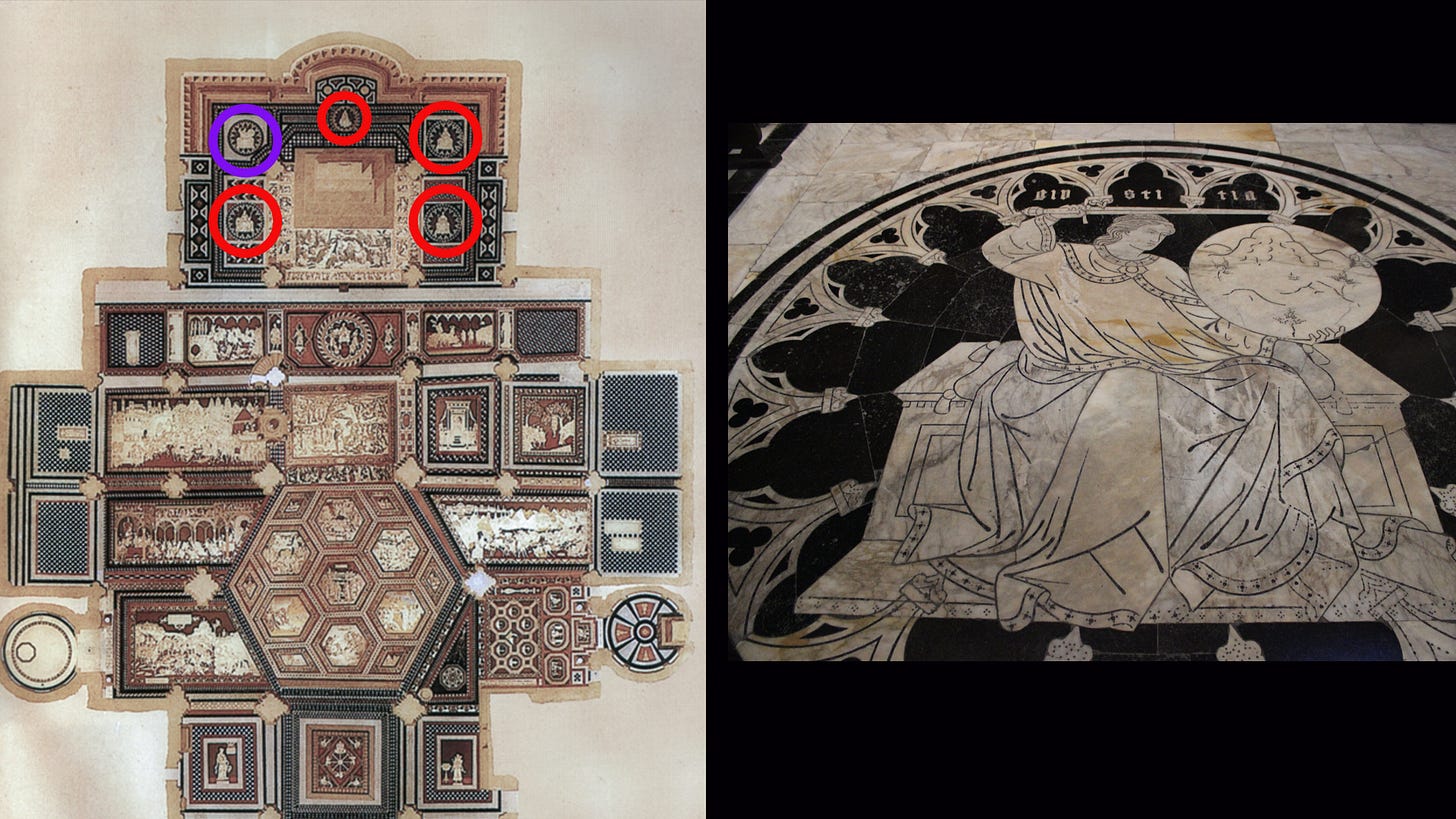

But by the time this painting was completed, a great many other, much more sophisticated, mosaics had also been created throughout the cathedral: the 5 intarsia circles in the choir area depicting the Four Cardinal Virtues and Mercy, dated to the early 1400s;

an extensive series of Old Testament scenes along the presbytery in the 1420s, featuring the likes of David, Goliath, Joshua, Samson and Moses, several of which are attributed to the celebrated Sienese artist Sassetta;

a 1434 scene on the right transept featuring Emperor Sigismund, and one beside it of The Death of Absalom created slightly more than a decade later;

and several works from the 1470s: The Seven Ages of Man by Antonio Federighi and two works by Francesco di Giorgio Martini: The Story of Jephthah and The Story of Judith.5

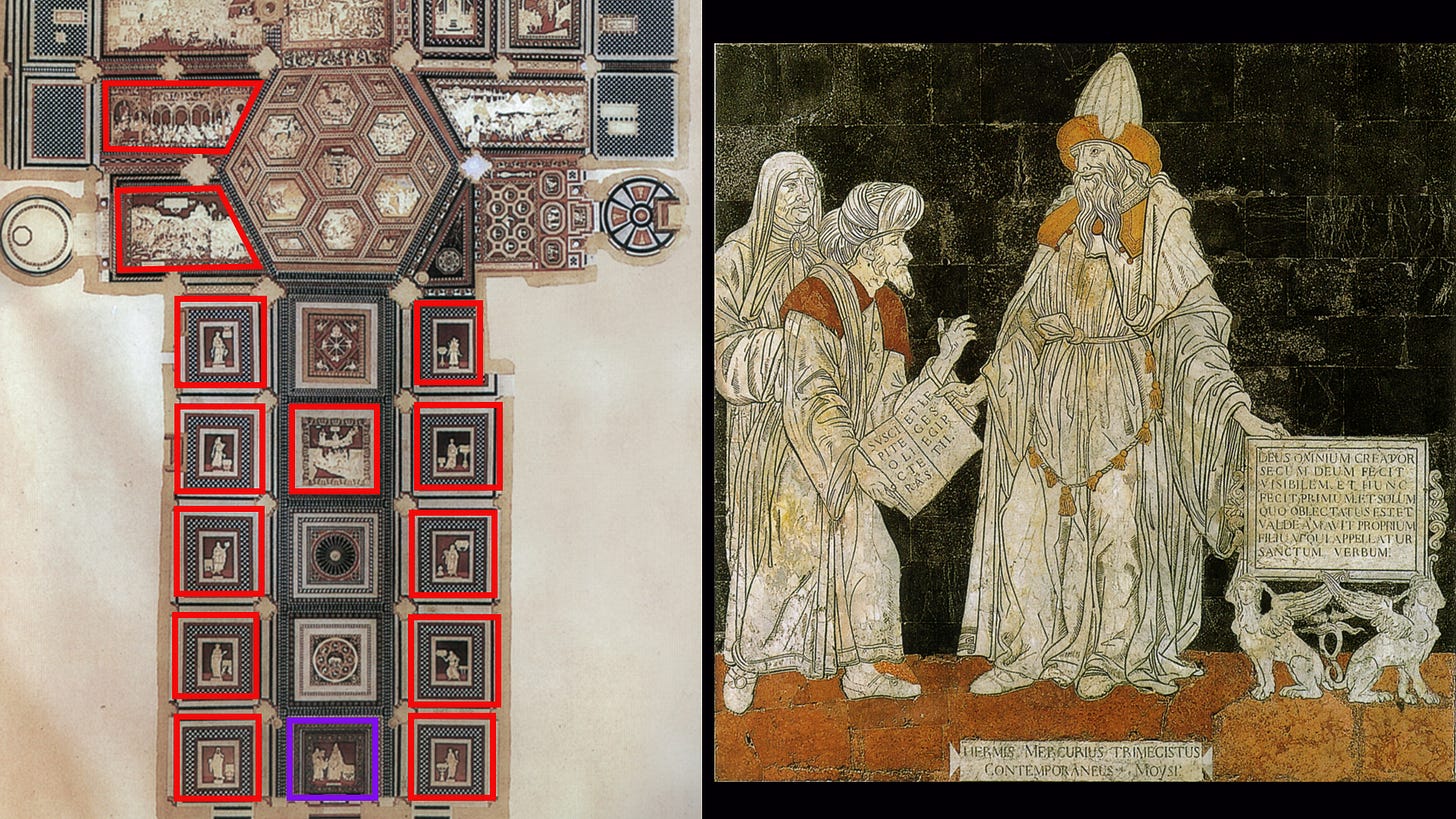

Meanwhile, by 1480, Siena cathedral’s extensive floor mosaic also contained three additional, arresting, images in its nave: Siena’s famous she-wolf surrounded by animalistic images of allied cities (c. 1360), a wheel with 24 “spoked pillars” containing a prominent eagle in the centre (c. 1373) and the standard medieval depiction of the Wheel of Fortune, with ancient philosophers (c. 1400).

At this point you might be forgiven for thinking that we’re almost done – but the truth is that we’ve only just begun, because 1480 marks a notable turning point in the history of the Sienese pavimento, as that is when Alberto Aringhieri began his hugely influential reign as Operaio del Duomo (rector of the cathedral administration).

Aringhieri, a Knight of Malta and highly accomplished scholar, was clearly responsible for many key features of Siena’s cathedral, from the St John the Baptist chapel to the Piccolomini Library – with Pinturicchio painting his likeness in both places

– but it’s on the cathedral’s celebrated floor where he clearly left his biggest mark, saturating the nave and adjacent aisles with his humanist inclinations (Hermes Trismegistus, Allegory of the Mount of Wisdom and no less than ten sibyls), while extending the left transept with two further scenes: The Expulsion of Herod and the only New Testament scene on the entire pavimento: The Slaughter of the Innocents.

But even Aringhieri hardly finished things off.

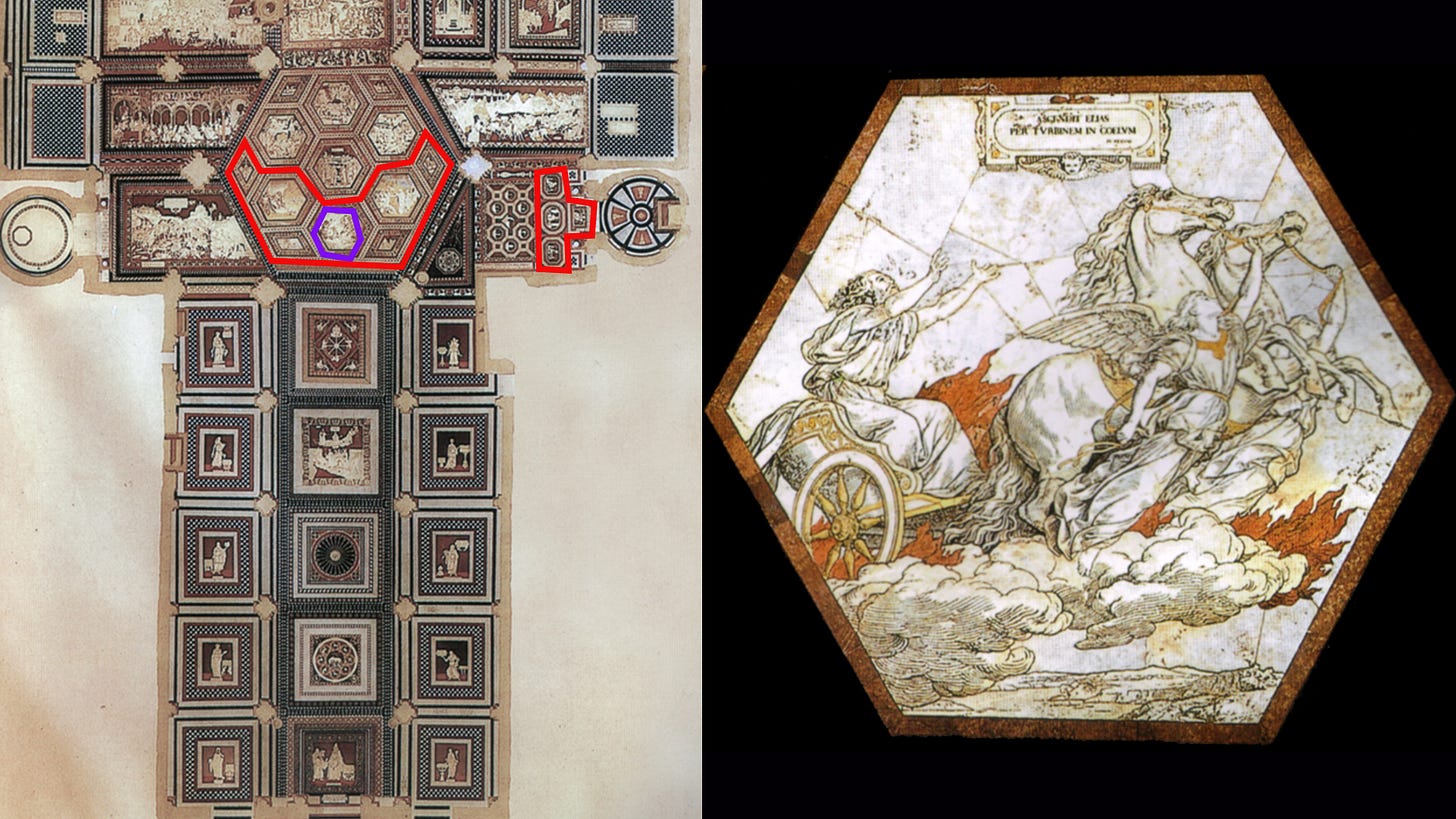

In the 1520s, in the hexagon under the cathedral dome, the last great artist of the formidable Sienese school, Domenico Beccafumi, crafted six separate Old Testament scenes, topped by two more rectangular images leading towards the presbytery (Moses Bringing Forth Water from the Rock and Moses on Mount Sinai) and a ninth marble intarsia of the Sacrifice of Isaac in front of the altar.

And then, over 350 years later, came even more, when the Purismo painter Alessandro Franchi added 7 more scenes to Beccafumi’s central hexagon series, while also crafting designs for four final images on the right transept of Religion and the Three Theological Virtues – themselves a revised version of four similar panels by Carlo Amidei and Matteo Pini a century earlier.

For over five and a half centuries, Siena’s artists, political leaders and civic administrators worked harmoniously together to produce one of the most coherent, comprehensive, and downright captivating works of art anywhere.

There’s a lesson in there for all of us.

Howard Burton

🎬 We’re currently in pre-production research of an extensive range of art films that will be filmed on location in Italy. All films are based on meticulous research and a strong narrative in combination with a wealth of beautiful images and filmed materials to provide viewers – from the armchair traveller to visitors to Italy to students and scholars – with a highly-informative and fully accessible exploration of Italian Renaissance art.

🎙️ 🎥 Make sure to subscribe for further updates about new films and also about our upcoming Exploring Art History podcast!

Sticklers may point out that works by Ghiberti and della Quercia are to be found in the adjacent Baptistery, along with additional works by Donatello – whatever.

The curious reader keen for a rigorous treatment of this issue is directed to Marilena Caciorgna’s Siena: The Pavement of the Cathedral.

The painting actually contains several simultaneous references to the saint at different stages of life, but my focus here, of course, is the cathedral floor.