The False Divide - Part 2

Still inappropriate

The other day I was speaking to the charming Florence-based artistic impressario Paola Vojnovic, who’d graciously invited me to give a talk on Sofonisba Anguissola for her studiolo to correspond with the upcoming release of our latest Renaissance Masterpieces art documentary, Sofonisba’s Chess Game (which, by the way, we will shortly commemorate with a month-long deluge of Sofonisba-related articles starting next Monday).

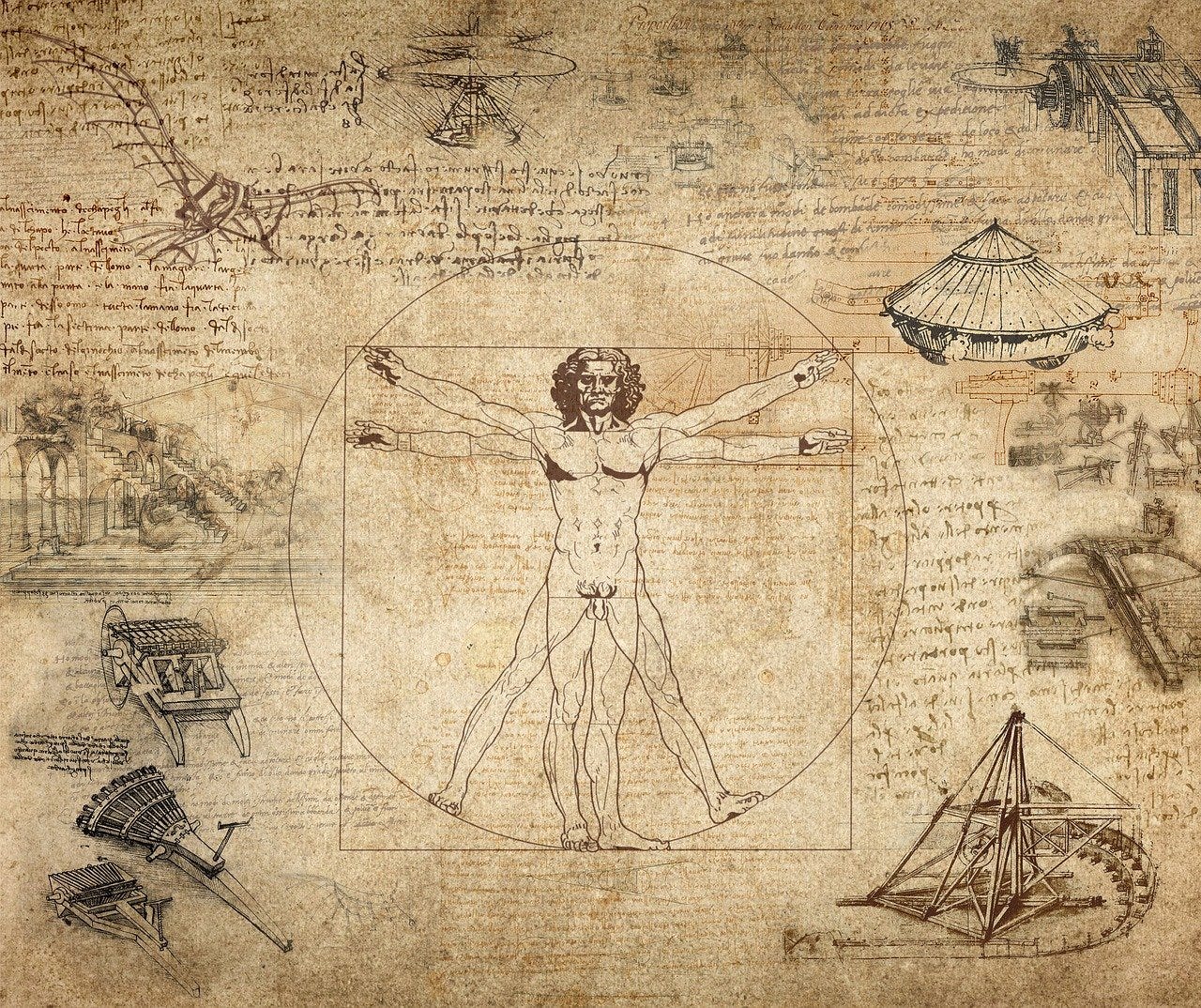

During our brief conversation, I was struck by the fact that Paola, like so many people in the world of art history I’ve spoken with over the past few years, seemed particularly intrigued by the fact that I have a physics background. Which got me thinking about how it might be worthwhile to write a follow-up to my last substack piece (The False Divide - Part 1), where I described how the modern dichotomy between “art” and “science” types would have bemused those living in the Renaissance (and many other eras too).

Because it’s important to appreciate that, as counter-intuitive as it might seem based on our all-too-prevalent societal stereotypes, there are a great many individuals out there today emphatically demonstrating the falseness of the so-called “art-science” divide on a daily basis. We just have to know where to look.

Here are a few striking examples:

Martin Kemp, one of the world’s leading authorities on Leonardo da Vinci, studied both natural sciences and art history at Cambridge before going on to write his landmark book, The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. For many years he wrote a regular column (“Science in Culture”) for the iconic scientific journal Nature.

Rebecca Goldstein is a bestselling novelist and philosopher who holds a PhD in philosophy of science and has written a large number of highly stimulating and well-researched books that seamlessly combine profound insights from both the natural sciences and humanities.

Peter Galison, a Harvard historian and philosopher with an academic background in both physics and philosophy of science, has written a number of beautiful books on the history of science (my personal favourite is Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps) and has recently turned his attention to producing captivating documentaries on a wide range of topics, from the development of the hydrogen bomb, to government secrecy to radioactive waste to black holes.

And then there is Peter Pesic. A long-time faculty member of one of the most impressively coherent liberal arts institutions in America (or, quite frankly, anywhere), St John’s College in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Pesic has a PhD in physics and has written numerous extremely insightful books and articles on the history and philosophy of science. I first came across him when reading his highly illuminating introduction to Levels of Infinity, Hermann Weyl’s selected writings on mathematics and philosophy which Pesic also carefully edited.1

All very impressive. But then I discovered that Pesic is also a concert pianist who has written several wonderfully insightful books on the overlap between music and science. Oh, and he’s also the director of St John’s remarkable Science Institute, which offers weeklong intensive seminars on historic texts in science and mathematics for teachers and other interested participants.

I could go on and on and on, but Pesic is perhaps the best one to end with, because, while I’ve never met him, I strongly suspect that in his own quiet, thoughtful, non-attention-seeking way, he’s a living instantiation of the answer to a question that’s surely on your lips by now:

If there are so many obvious counter-examples to the flagrantly inappropriate “science/humanities” dichotomy that suffuses so much of our current thinking, why on earth is it still so overwhelmingly prevalent?

Well, aside from the fact that so many contemporary education programs strongly reinforce this false divide by continually “streaming” high school students into non-overlapping intellectual avenues, I suspect that possessing a simple key that enables us to unreflectively pass judgement on whatever the world throws our way will always hold considerable appeal, particularly if it makes us feel good in the process.

For all those out there who’ve suffered painful high-school memories of math or physics class – and there are, sadly, a great many who fit that description – the prospect of being able to straightforwardly declare that our “inherently artistic” brains simply work differently than those of our more “scientifically-oriented” colleagues (as opposed to the vastly more likely conclusion that we simply had an incompetent, and often profoundly insensitive, math or physics teacher) is naturally particularly alluring.

But that hardly makes it right.

To take but one obvious example:

The combination of logic, empirical evidence and creative insight required to develop a bold new interpretation of a specific set of historical events is effectively indistinguishable from the formal thought processes required to come up with a new scientific theory.

The domain particulars, naturally, are very different. But then so are those, typically, between one historical period and another, or between history and philosophy, or between different scientific subspecialties.

Of course, there are often significant methodological differences between disciplines. In particular, a celebrated distinction between the sciences and the humanities, and one which greatly increases the appeal of the former in these particularly insalubrious, hyper-polarized times, is that studying the coolly objective natural world or the highly abstract realm of pure mathematics, seems blissfully independent of the annoying prejudices and irrational biases that we humans are sadly riddled with.

But it turns out that when you look closer, even that divide might well be much more porous than we might have imagined, given that both science and mathematics are nonetheless human activities practiced by humans.

In their 2024 book The Blind Spot, for example, two physicists and a philosopher describe how they believe that science should be explicitly reformulated to incorporate human-centric experiences, while the bestselling 2007 book by Daniel Levitin, This is Your Brain on Music, captivatingly weaves together the subjective experience of the music lover with the more general conclusions of contemporary neuroscience.

Meanwhile, my own experiences through many Ideas Roadshow filmed conversations very much supports this sense of highly frequent crossover between the objective pursuits of science and our all-too-human interpretations: a violinmaker deducing, after a series of rigorous empirical experiments, that there was no objective distinction between the sound of a Stradivarius and other violins, a physics Nobel Laureate puzzling over what, exactly, makes a banjo sound like a banjo, and a steady parade of scientists straightforwardly relating how aesthetic factors consistently play a strong role in framing their research agendas.

In short: it’s complicated. And very, very interesting.

*** If you have not read Part 1 yet, click below:

Howard Burton

Hermann Weyl, by the way, is quite possibly the most criminally underrated thinker of the 20th century, whose work in mathematical physics (together with that of the even more neglected Emmy Noether) led directly to the formalism on which all modern particle physics understanding is based.