So here we are, the final article in our “Sofonisba September Series” to complement the release of our new art documentary, Sofonisba’s Chess Game.

We’ve talked about Sofonisba’s style, her family, her remarkable teaching skills and even her apparel. We’ve plunged into her Chess Game and discussed both the overarching message and a wealth of intriguing, illuminating details. We’ve even tackled – albeit somewhat begrudgingly and in a fairly idiosyncratic way – the complex issue of to what extent Sofonisba should be regarded as a “feminist painter”.

But now it’s time to move to what, for me, is by far the most vexing issue of the entire Sophonisba story: What on earth happened to all of her paintings?

In Sofonisba’s Lesson,1 Columbia University art historian Michael Cole, desperately trying to establish some order in the highly chaotic Sofonisba universe, ambitiously attempted to catalogue all publicly available works associated with her in four primary groups:

Documented Works (15)

Attributions Largely Accepted By Specialists (19)

Works with Contested or Insufficiently Discussed Attributions (24)

Works Attributed to Sofonisba but Accepted by Few Specialists (90)

These were followed by two additional categories, naming the 93 works that are now lost or in private collections:

Works Documented in Private Collections, Locations Undisclosed (26)

Works Attributed to Sofonisba without Illustrations since 1900 (67)

The first obvious point to make is that there is a marked inverse relationship between our attributional confidence and the number of paintings under consideration: the less confident we are that a painting was actually created by Sofonisba, the more of them there are to consider.

We are quite sure of the 15 in the first category, reasonably certain of the 19 in the second, relatively hopeful of the 24 in the third, and pretty darn sceptical of most of the 90 in the fourth.

Doubtless Cole’s list has provoked strong disagreement (if not outrage) from many museum curators around the world. It must be somewhat galling to learn that the work you’ve long been trumpeting as a Sofonisba has been summarily placed by Cole in his third, or perhaps even fourth, category.

But while Sofonisba scholars might well debate his specific allocations, very few, I imagine, would argue the essential point that the overwhelming majority of paintings blithely ascribed to Sofonisba are much more problematic than most people realize.

And even more noteworthy still: of the 15 works placed in his first category, a whopping 13 are from before she left for Madrid (the other two are from after she returned to Italy), while roughly half of those in the second category are also from her youthful days in Cremona. In other words, the overwhelming majority of paintings that we can confidently attribute to Sofonisba come from before she went to Spain around the age of 27.

And while several entries in the second and third category belong to her Spanish period, all told there are only six readily extant works – five religious scenes and one portrait sketch – that are explicitly put forward as having been painted after her time in Spain:

Which means that even if we are prepared to accept all six – and I am definitely not, as that would mean incorporating the decidedly underwhelming Madonna dell’Itria Carried on a Sarcophagus into the Sofonisba corpus2 – that still leaves an exceptionally large gap in the output of a phenomenally talented artist renowned for her diligence and enthusiastic commitment to painting: firmly attributing only half a dozen works to her from the entire second half of her very long life.

Well, you might think, perhaps she just got fed up with painting?

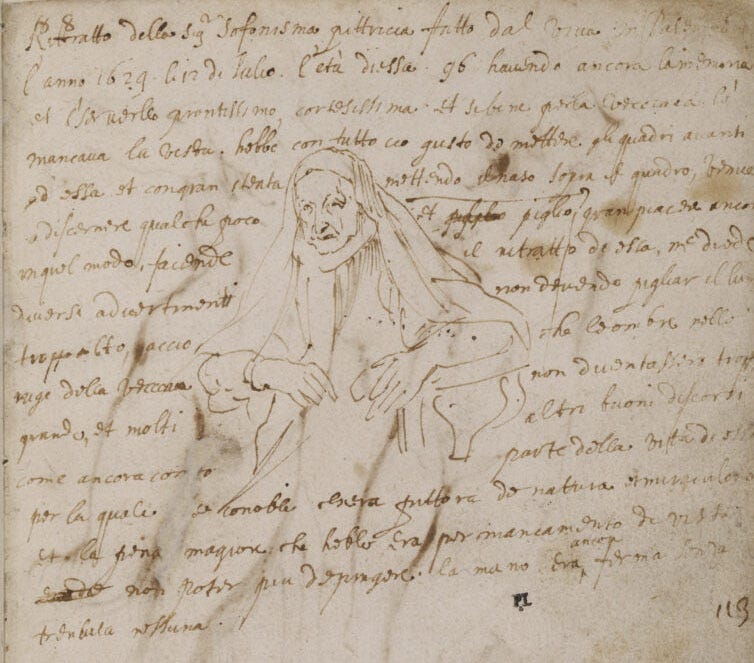

Unlikely, as that doesn’t jibe very well with the paltry documentation that we do have, that of Van Dyck’s famous recording in his Italian Sketchbook of his encounter with an aged Sofonisba in Palermo in 1624.3

“Portrait of the painter Sofonisba, made from life at Palermo in the year 1624 on 12 July, when she was 96 years old4 and still preserved her memory and great sharpness of mind, being most courteous, and despite her failing eyesight due to old age she nevertheless liked to place the paintings in front of her and, very attentively, pressing her nose up close to the picture, was able to make out a little of it and derived great pleasure from doing so.”

That doesn’t exactly sound to me like someone who had had enough of painting.

Moreover, Van Dyck goes on to add that Sofonisba, ever the teacher, didn’t hesitate to give him several very valuable tips while he was constructing her portrait.

“When I did her portrait, she gave me several pieces of advice on not to raise the light too high so that the shadows should not accentuate the wrinkles of old age and many other good suggestions, and she also told me about parts of her life, from which it is apparent that she was a miraculous painter from life, and her greatest torment was not being able to paint anymore because of her failing sight, though her hand was still steady and untrembling.”5

In short, we can pretty confidently assume that Sofonisba had neither become indifferent to painting as she progressed through her long life, nor forgot essential aspects of her well-honed artistic technique.

So where on earth are the works she made during the 5 years she lived in Paternò and the roughly 35 that she lived in Genoa (to say nothing of the last 10 years she lived in Palermo)?

The most comprehensive attempt I’ve seen to track this thorny question down comes from Cecilia Gamberini’s impressive book on Sofonisba from the Lund Humphries Illuminating Women Artists series, where there are a few specific mentions of paintings that sadly don’t appear to have survived, such as the portrait of the Virgin Mary she was said to have presented Empress Maria of Austria (Philip II’s sister) when she passed through Genoa in 1581.6

Meanwhile, in 1583, the Infanta Catalina Micaela, the younger daughter of Philip II and Elizabeth of Valois, met up with Sofonisba on her way to Turin, and for years this portrait was believed to be Sofonisba’s way of commemorating the occasion,

as was this one of her elder sister Isabella Clara Eugenia (now hanging in the Spanish Embassy in Paris), who passed through the region some fifteen years later on her way to the Low Countries.

But in their 2019 exhibition on Sofonisba and Lavinia Fontana, researchers at the Prado attributed the first to Alonso Sánchez Coello and the second to Giovanni Caracca.

Meanwhile, according to Gamberini:7 “That Sofonisba continued to paint in Genoa is demonstrated by her interactions with the most important painters working in the city at the time, including Luca Cambiaso, Giovanni Battista Castello8 and Giovan Battista Paggi”, and that Sofonisba also taught Pietro Francesco Piola who boasted that “he had been the pupil of the most illustrious female painter in Europe”.

Bernardo Castello, the younger brother of the aforementioned Giovanni Battista, and the father of the famed Ligurian artist Valerio Castello, seemed to have particularly close contact with Sofonisba, who was selected to be the godmother to one of his sons. Gamberini also maintains that Bernardo Castello was the author of a later copy of Sofonisba’s Spanish self-portrait at the Musée Condé in Chantilly.9

Two Sofonisba biographers note that during her many years in Genoa she created “many excellent portraits” and religious subjects, most of which were said to have entered the private collection of the father of the Doge of Genoa and somehow became mysteriously lost. There are regular accounts of senior civic and literary figures in the Republic of Genoa singling her out for praise and many accounts of Sofonisba works in Genoese inventories.

But almost no paintings.

And then there’s the other related, and equally obvious, question that I’ve often pondered as I desperately tried to navigate my way along the frustratingly intermittent trail of Sofonisba bread crumps:

Where are all the documents?

Surely Sofonisba, as a highly educated, cultivated person of noble background and impeccable reputation, would have left behind a great deal of personal correspondence – not to mention many drawings, sketchbooks and incomplete paintings – upon her death. Where are they?

It’s not unusual, of course, to be confronted with a palpable lack of documentation concerning famous artists. The tragedy that there are almost no surviving preliminary sketches by Botticelli, for example, is generally regarded as being due to the fact that nobody was looking after them, since the potential beneficiaries were on record as having officially declined the inheritance – an action generally signifying that the accumulated debts prohibited any otherwise disposed relative to claim ownership of the legacy. But while we know that Sofonisba regularly faced financial issues throughout her life, nothing of that sort seems to be happening here.

Indeed in 1632, some seven years after she died (and quite possibly to mark the centenary of her birth), her widow Orazio Lomellini placed this moving commemorative plaque in the chapel dedicated to Saint Luke in Palermo’s San Giorgio dei Genovesi.10

And while Sofonisba’s fame at this point was likely nothing like it was when her father was intensely distributing her masterpieces to nobles throughout the land 80 years earlier, or when she was actively involved in Philip II’s Madrid court, she had clearly not entirely faded from the public eye, as witnessed by Van Dyck’s determination to seek her out, as well as the many written accounts of her life from Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Pedro Pablo de Ribera, Rafaelle Soprani, Filippo Baldinucci, and others.

So why, on earth, do we know so little about what she did in the last 50 years of her life?

Sofonisba Anguissola left us a significant number of magnificent paintings, replete with the usual stimulating combination of subtle nuance and interpretive ambiguity that you would expect from an artist of her calibre, enough to keep art lovers vigorously engaged in debating the details of her works for centuries.

But she should have left us a good many more.

And that, surely, is the greatest Sofonisba mystery of all.

Howard Burton

Below is the trailer of our new film Sofonisba’s Chess Game. Visit the film page below:

This is the last time I’m going to refer to this wonderful book (I think); all Sofonisba fans really owe it to themselves to go out and buy it (right after watching our film, of course).

This painting is discussed in more detail in my 6th post in this series, Searching for Clarity.

Barbara Tramelli, in her 2016 article, “Sofonisba Anguissola, ‘Pittora de Natura’: A Page from Van Dyck’s Italian Sketchbook”, remarks that this entry is unique among (at least this particular) Italian Sketchbook, as it is both the longest account and only written record of a personal event, implying that Van Dyck made the effort due to the significant impact the meeting had on him.

The general scholarly consensus is that when Van Dyck visited Sofonisba she was roughly 92, rather than 96, as he mentions here.

According to several sources (i.e. Raffaele Soprani and Filippo Baldinucci), Van Dyck declared that he learned more from his discussion with Sofonisba than from the works of more famous painters.

From the 1609 biography of Sofonisba by a Spanish canon of Rome’s Saint John Lateran, Pedro Pablo de Ribera.

Referencing Roassana Sacchi’s articles in the 1994 exhibition catalogue, Sofonisba Anguissola e le sue sorelle.

Known as “Il Genovese” to distinguish him from another, earlier, Giovanni Battista Castello known as “Il Bergamasco” who became court painter and architect to Philip II, and who Sofonisba must have encountered during her time in Spain.

As always, it seems, there are debates – some deny Castello’s authorship, while also opining that Sofonisba’s original in the Musée Condé is not actually a self-portrait (see here, for example).

The inscription reads (from Gamberini’s Sofonisba Anguissola, p. 122): To his wife Sofonisba, of the noble house of Anguissola, placed among the illustrious women of the world for her beauty and extraordinary gifts of nature, and so distinguished in portraying human images that none of her time could equal her; Orazio Lomellini, struck by immense grief, placed this final mark of honour, small for such a woman, but the greatest for mere mortals, 1632.