Unlocking The Vaults

Look up

Today I’d like to explore the many fascinating relationships between the vault in the Piccolomini Library and two of the most famous ceilings in the history of art: that of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura. As mentioned in last week’s post, Only Connect, I first came across this notion in Gyde Vanier Shepherd’s 1993 doctoral thesis, but it quickly became apparent to me that such deep links have been actively discussed by art historians for decades, if not centuries.1

None of this, in other words, is “new” from an art historical standpoint. But that’s not the point. My aim isn’t to bring forth a shocking new discovery, still less to prove that some famous artists were less original than the usual stereotype of superhuman genius traditionally allows, but rather to highlight the intriguing historical and artistic context in which they were working – which not only prompts compelling correspondences between different artworks, but also gives us a better appreciation of the actual innovations they developed, and why.

So let’s launch in.

The first thing to say is that the elaborately detailed frescoes in the Piccolomini Library were hardly the first ones attempted by Pinturicchio, who’d worked on a great many such comprehensive programs over his career. Strongly influenced by Perugino, whom it’s widely believed he assisted with his contributions to the famous 1480-81 wall series in the Sistine Chapel,2 Pinturicchio and his workshop went on to produce a vast array of comprehensive fresco cycles, mostly in Rome, for some of the most influential patrons imaginable.3

Indeed, there’s a strong argument to be made that, when he signed the 1502 contract with the Sienese cardinal Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini for the decoration of the Piccolomini Library, Pinturicchio was the most celebrated fresco painter alive.

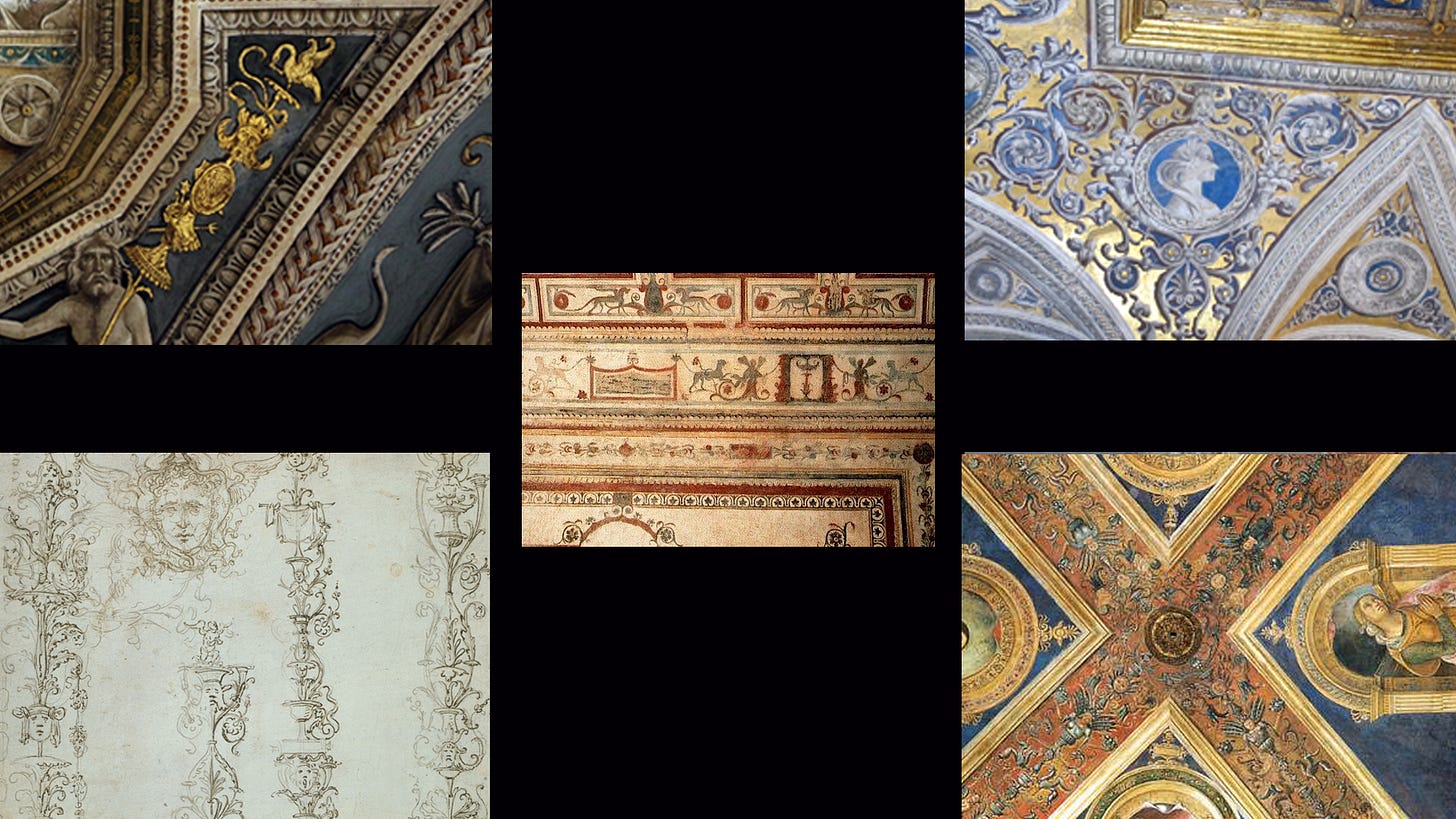

He was also, famously, one of the “early adopters” of one of the most vigorously raging artistic fashions of the day: the intricate, spindly, fantastical images known as “grotesques” – so called because they were found throughout the recently rediscovered, long-buried caves (“grotte” in Italian) containing Nero’s elaborate Domus Aurea (Golden House).

As it happens, that 1502 contract I just mentioned explicitly mandates that Pinturicchio should paint the library’s ceiling

“with those fantasies, colours and divisions that he judges to be the most beautiful and eye-catching in the style and designs that today are called ‘grotesques’...”

A close examination reveals that he did indeed load the upper realm of the library with beautiful grotesques, but interestingly, only the triangular “pendentives” and “severies” over the wall’s narrative scenes that culminated in the large, relatively flat ceiling,4 not the ceiling itself: a large rectangular space divided into a series of separate detailed scenes displayed in different types of geometric enclosures.

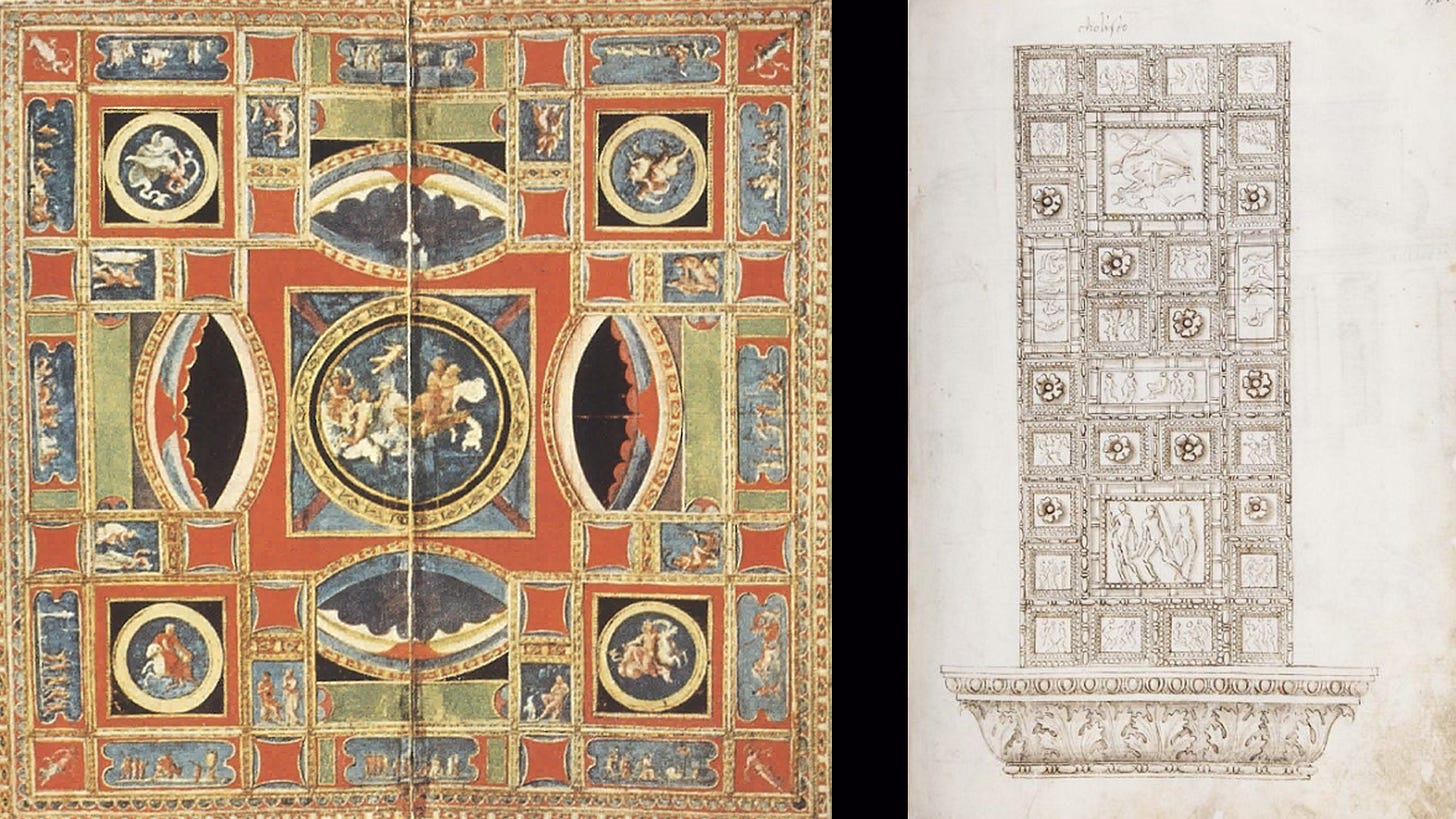

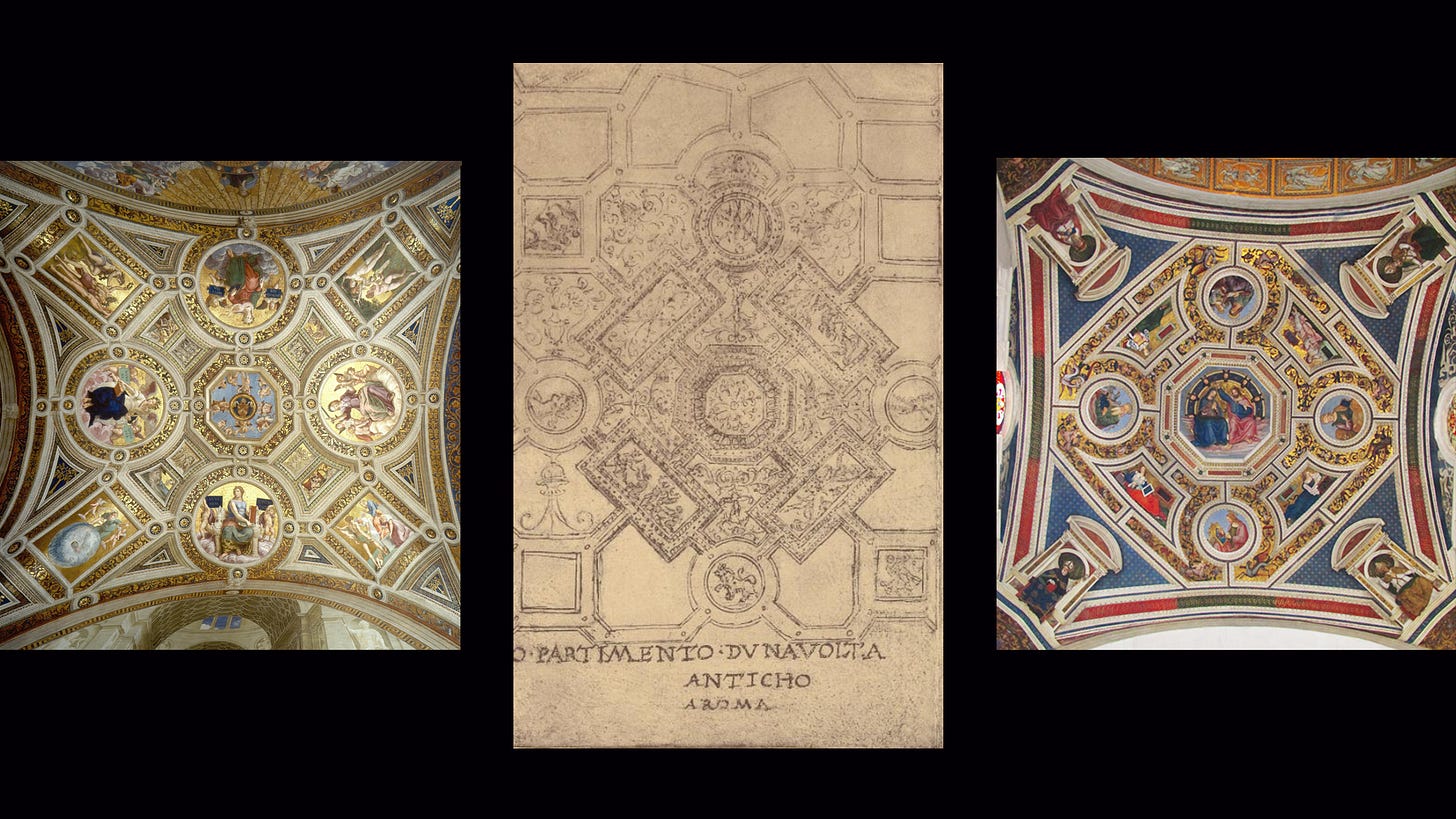

As it happens, this structural format that Pinturicchio chose for the Piccolomini Library ceiling is an avowedly antique one too: clearly inspired by – one might even say “borrowed from” – a combination of the so-called Volta Dorata, also from Nero’s Golden House, and other documented ancient Roman decorations, such as a drawing of stucco details on the underside of an arch in the Roman Colosseum in the so-called Codex Escurialensis. Well, OK, you might say, clearly Pinturrichio was a huge fan of ancient Roman artistic traditions. But the key point here is that he was hardly the only one.

Only a few years after Pinturicchio finished working on the Piccolomini Library project, one Michelangelo Buonarotti was being pressed into service by Pope Julius II to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

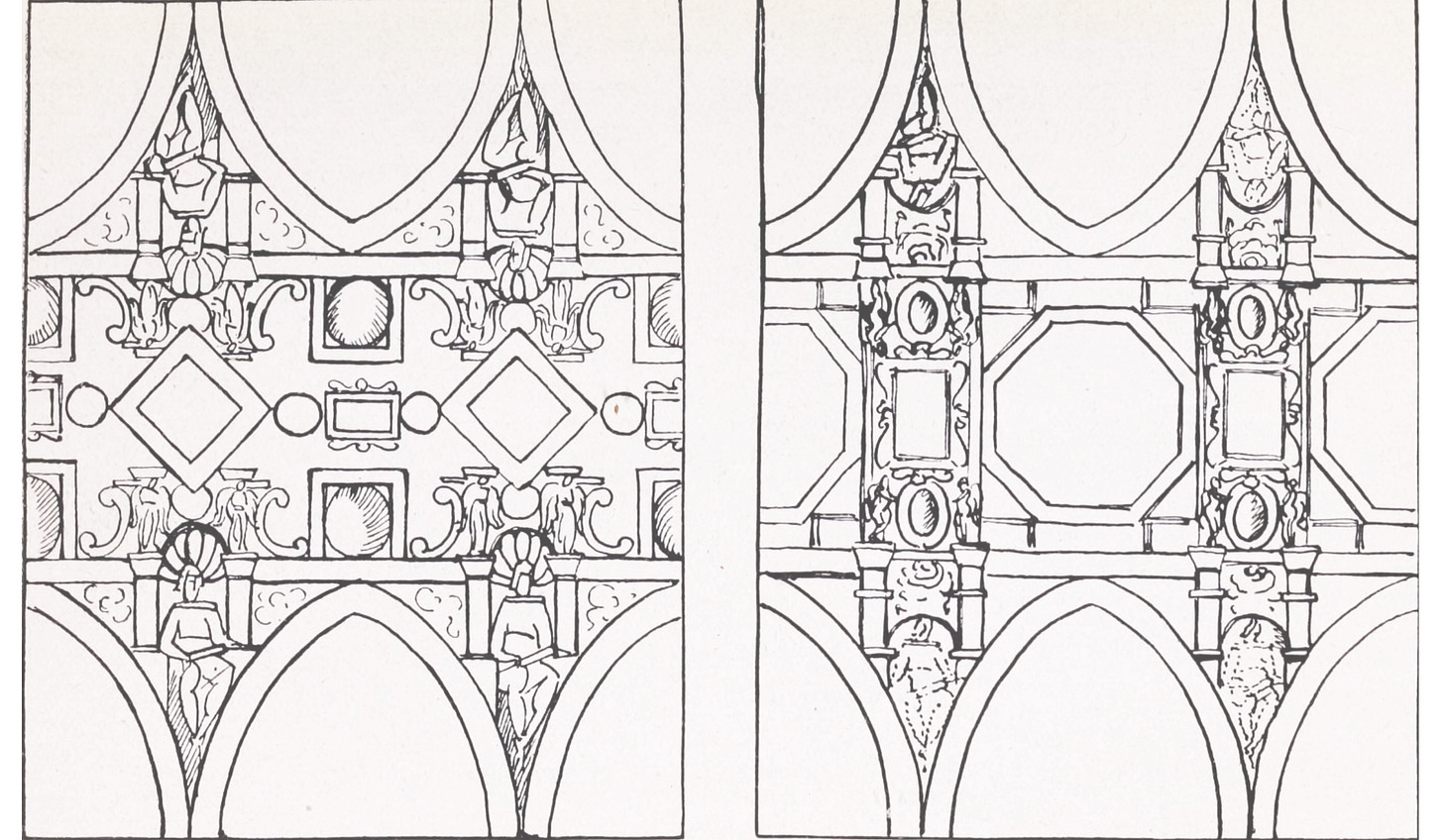

Before Michelangelo got started, this ceiling was strikingly similar to that of the Piccolomini Library, with its series of pointed severies thrusting into a large, rectangular, open space filled with a pattern of stars in the night sky.5

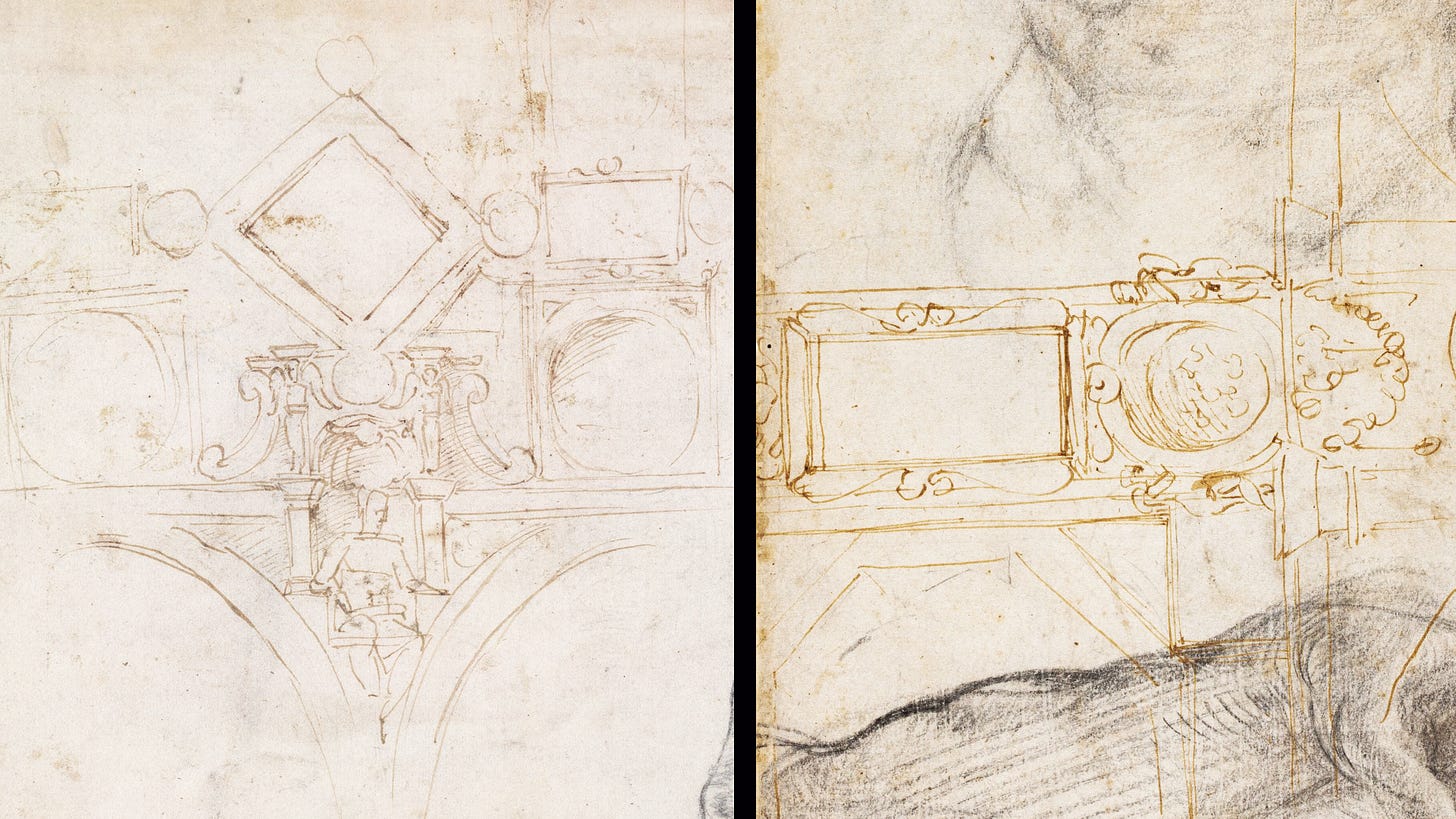

But the similarities don’t end there, because we know that Julius’ original plan for the Sistine Chapel ceiling was to fill that open space with precisely the sort of geometric shapes that Pinturicchio used in the Piccolomini ceiling, with figures of the twelve Apostles lying featured in the pendentives.

After several frustrated attempts to work within this rigid, faux-ancient structure,

Michelangelo famously approached the pope to ask if he could do something different instead – and Julius, to his eternal credit, gave him free reign to indulge his creative genius to the fullest, thereby enabling him to develop the timeless masterpiece that we all know and love today, over 500 years later.

Now, there’s no evidence at all for this, but it’s hardly inconceivable that Michelangelo had personally witnessed Pinturrichio’s Piccolomini ceiling as it was being painted, given that by 1504 he was on record as having delivered 5 of the 16 statues that he’d agree to produce for the nearby Piccolomini altarpiece inside the Siena cathedral (he never, as it happened, delivered the remaining 11).6

Perhaps he’d peeked inside the Piccolomini Library after a jaunt to Siena, looked at the vault in progress, and muttered to himself that he could surely do better. We’ll likely never know.

But what we do know with confidence is that at precisely this time, another incomparable Renaissance master was already on site in Siena helping Pinturicchio out with his great Piccolomini Library project – the great Raphael, then only 19-20 years old. Giorgio Vasari had long maintained as much in his celebrated Vite, but his claims lay disregarded for centuries until Raphael’s strikingly detailed modellos for two of the Piccolomini frescoes were discovered.

(Those somehow still sceptical might wish to take a closer look at the ninth fresco in the series where Pinturicchio drew himself in the foreground, gazing appreciably at the precocious Raphael - see below)

And while we have no evidence that Raphael participated in the Piccolomini Library ceiling (something Vasari never mentioned), it’s awfully hard to imagine that he was completely oblivious to it.

This matters, because it turns out that a few years later – exactly when Michelangelo was struggling away on the Sistine Chapel ceiling – Raphael found himself working away on his very own, soon-to-be immortal vault commissioned by the frenetic Julius II: that of the so-called Stanza della Segnatura – the room that contains, among several other wonders, the celebrated School of Athens.7

And all of that was happening at precisely the same time that Pinturicchio had also been summoned to Rome by the indefatigable pope to paint the choir vault of the church of Santa Maria del Popolo – which, notably, bears an uncanny structural similarity to the one in the Stanza della Segnatura.

As you might imagine, it’s a matter of considerable debate as to who – Raphael or Pinturicchio – first influenced whom; and we’re unlikely to ever know for certain. Indeed, perhaps it was a combination of the two, given their previous close working relationship.

But surely the strong resemblances of the two ceilings, from the central octagon, to the four symmetrical tondos to the grotesque-filled boundaries to even the use of a unique trapezoidal shape, is more than mere coincidence. Moreover – and likely far more significantly – both vaults are obviously related to an ancient stucco vault from Hadrian’s Villa, as recorded by Giuliano da Sangallo in his illuminating Taccuino Senese.

Perhaps even more significantly still, both the Stanza della Segnatura and Santa Maria del Popolo vaults seemed to have been reconfigured by Donato Bramante, Julius’ chief architect, in a profoundly similar way to what Michelangelo was doing with the Sistine chapel ceiling, well before any decorations had been painted on them whatsoever.8

Something truly remarkable was going on in Roman vaults in the first decade or two of the 16th century. And the more you learn, the more engrossing the story becomes.

Howard Burton

🎬 We’re currently in pre-production research of an extensive range of art films that will be filmed on location in Italy. All films are based on meticulous research and a strong narrative in combination with a wealth of beautiful images and filmed materials to provide viewers – from the armchair traveller to visitors to Italy to students and scholars – with a highly-informative and fully accessible exploration of Italian Renaissance art.

🎙️ 🎥 Make sure to subscribe for further updates about new films and also about our upcoming Exploring Art History video podcast!

Those interested in sampling things for themselves are directed to the particularly insightful 1962 article by J. Schulz’s 1962: “Pinturicchio and the Revival of Antiquity”.

Which also contains works by Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli and Luca Signorelli.

The Bufalini Chapel in Santa Maria in Araceoli (1484–86), the Palazzo dei Penitenzieri and Palazzo Colonna (1485–90); the Basso della Rovere chapel and Della Rovere chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo (1485–92); the Villa Belvedere (1987-88), and the Vatican apartments of Alexander VI.

As the Piccolomini Library, like the Sistine Chapel, is essentially a box, these are not real pendentives that support a circular dome on top of a rectangular room – see here, for example – just as the “severies” are not segments over actual arches; they are instead instances of Pinturicchio’s fondness for illusionistic architecture.

Most scholars believe that the specific stellar arrangement shown here likely had a unique astrological significance, illustrating a particular moment associated with the birth, or ascendance to the papacy, of Sixtus IV, the pope who rebuilt and decorated the chapel that still bears his name.

15 statues of his own and one left uncompleted by Pietro Torrigiano (who’d broken Michelangelo’s nose years earlier) that he’d been requested to finish – see my Jan 5 post, Subjective Expertise for more details.

Perhaps even more intriguingly still, work on the room’s celebrated ceiling is believed to have been started before Raphael’s arrival by the artist Il Sodoma, whom Raphael might well have first encountered in or nearby Siena, and whom it’s widely believed that Raphael depicted standing next to him in The School of Athens.

For the structural modifications of the Stanza della Segnatura see, for example, John Shearman’s article “Raphael as Architect”, p. 396; for Bramante’s efforts in Santa Maria del Popolo, an easy reference is this 2015 The Roman Anglican post by Edoardo Fanfani, while the history of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling is rigorously detailed in Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt’s chapter, “Michelangelo’s Early Projects for the Sistine Ceiling: Their Practical and Artistic Consequences”, in Michelangelo Drawings, freely available on the Internet Archive.